Disposable Engines

Strategy through the lens of a $20 Polaroid

Last week we drove 6,200 kilometers from Montréal to Whitehorse. It’s nice to be home. Laurie wrapped up her Master’s degree and we decided to head back West for a couple of years. Now I’m sitting in my old coworking space, Yukonstruct. Even this far from California, I can almost feel the hum of Silicon Valley reverberating up the coast – and it’s sparked some thoughts about AI, economics, marketing, and strategy.

On trips like the one we just did, I like to purchase a cheap disposable camera with about two dozen exposures. I’m hardly a photographer, but there’s something super fun about this ritual. The pause. The click. The reveal. Part of the fun of it is that you don’t ever quite know what you’re going to get.

Same goes for building a new field or growing a nascent scene. Not many people do that. There’s not as much of a playbook as there is for start-ups. But, just like you can build a timeless photo album with disposable cameras – you can use disposable engines to create a self-sustaining project.

In 2016, Donald Mackenzie wrote An Engine, Not a Camera, illustrating how financial theories don’t just describe markets but eventually affect them. Ideas in behavioral economics aren’t images of how we make decisions, but memes that take root and become self-fulfilling prophecy – until the illusion breaks. In the Protocol Reader, these things were referred to as world engines.

Last year, my colleague Venkatesh Rao wrote A Camera, Not an Engine, inverting Mackenzie’s idea to explain how LLMs work. They’re not automatons, doing our work for us, but telescopes that allow us to traverse the universe of human knowledge with our feet firmly planted. Artificial intelligence, thus far, is educational – not operational. As a technology, it is a world camera.

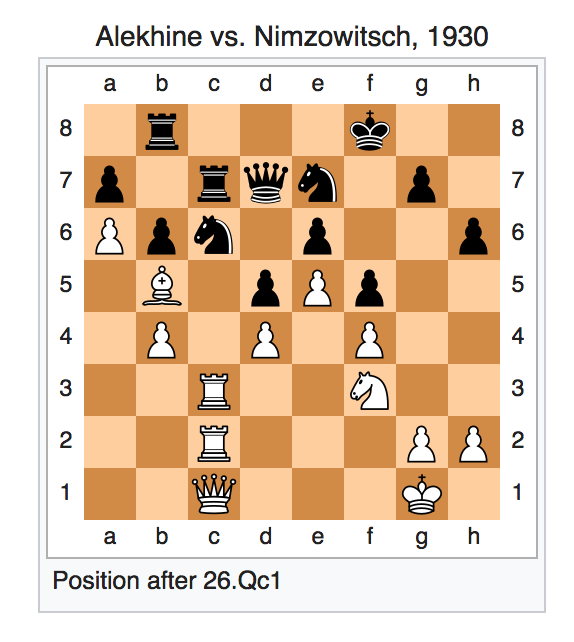

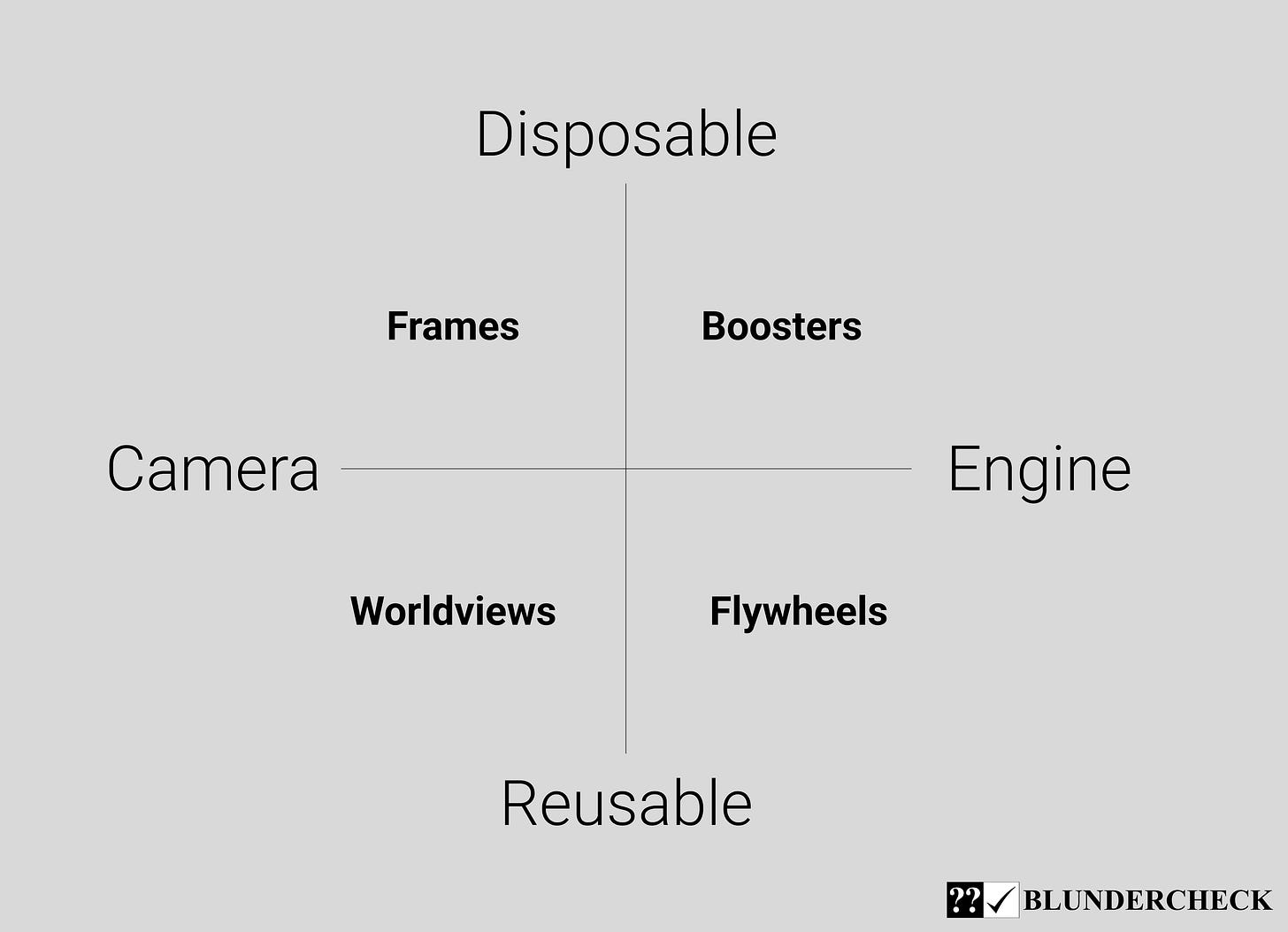

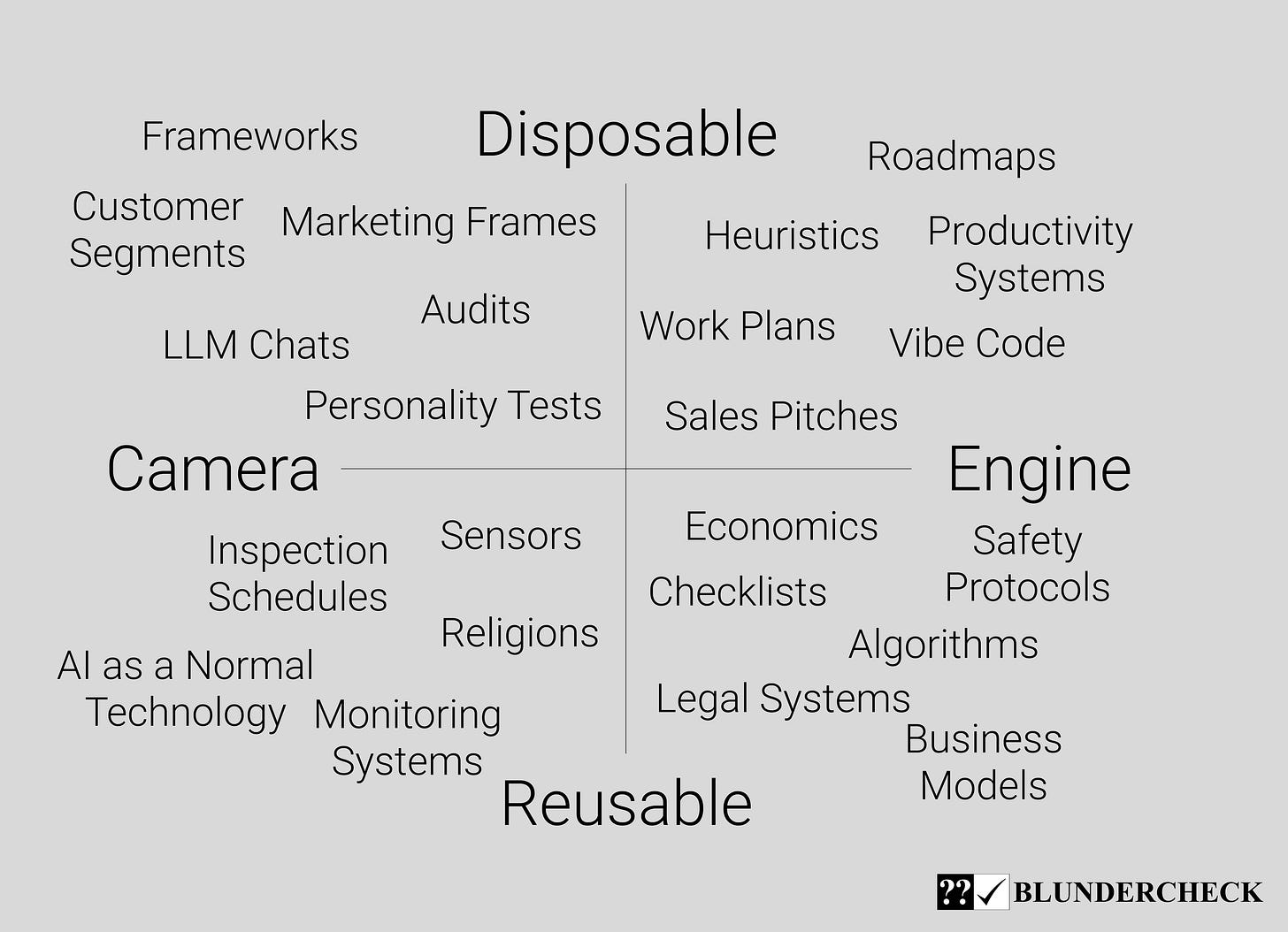

We can increase the grain of this analysis by adding another dimension: disposability.

In the metaphorical sense, disposable cameras include things like clever marketing reframes of existing products, personality tests, LLM chats, and audits. These are frames that provide a snapshot of a thing, often from a creative or promisingly objective angle. Reusable cameras are persistent ways to see the world: religions, monitoring systems, inspection schedules, and classes of technologies like artificial intelligence.

Reusable engines are what everyone wants. A business model that churns out profits. An economic theory that guides monetary policy. Reliable mechanisms for public health and safety. On the flip side you have disposable engines – which, I will argue, are very underrated. Things like rules of thumb, hacks, sales scripts, vibe code, prototypes, experimental protocols, personal grudges.

Classification errors along the camera-engine and disposability continuum lead to big problems. For example, the field of behavioral economics stumbled headlong into a replicability crisis. Once startling conclusions about urinal design, advertising tricks, and road safety turned out to have no scientific basis. Around the same time, we saw evolutionary psychology boom. Again, the ideas from that field don’t explain human decision-making but power it. These are engines disguised as cameras.

It’s bad to mix up where things belong on this 2x2. Part of the reason that we do make those mixups is because frames and boosters are underrated. So we assume that the things we’re building are more durable and valuable than they are.

Many people think they operate in a strategic space when they’re really in a tactical battle. You don’t yet need strategy. Amateurs (and I mean that in a good way) benefit more from not screwing up than by being strategic. Field building and startups, two types of amateurish ventures, face a double problem. They must simultaneously solve for growth and fit. And it’s not obvious how to do that, which is why you need a variety of cameras and engines – something you cannot afford if you over-invest in one worldview or flywheel.

Eventually, you’ll find some things that work. Plastic engines can be graduated into the permanent, powerful spine of your venture. Or they can be used up and thrown away, having got you into a new market or position. The trick is having sufficient optionality and firepower.

Let’s test this idea in an unusual laboratory: the chessboard. A notable tactic in chess is to align heavy pieces (rooks and queen) along a file. That assemblage is known as a battery and it points dangerously at one’s opponent. Other pieces can sit along that file, propelled by rooks that act like the boosters of a multistage rocket. A battery is a disposable engine – one that you can sacrifice just as easily as you can fortify. I still play chess competitively and these kind of quasi-positional tactics have become essential as I’ve migrated more towards shorter time formats.

Last year someone suggested that the Summer of Protocols program was doing too many things. That was relatively correct. From their perspective, there was no substitute for a reusable worldview or flywheel. But they weren’t trying to precipitate something entirely new, in an uncertain and hostile environment. For that, you will need to create, deploy, and dispose new types of engines.

Startup teams have a better intuition for this than field builders. Common wisdom in venture land suggests that you might end up building something completely different than you set out to. It’s also a slightly more straightforward game: make money. The means are more easily partitioned from the ends. For more complex or abstract goals, like improving public health, taking human civilization interstellar, or starting a new field of study from scratch, it’s easier to get attached to your projects.

The purpose of disposable engines is twofold: they are both propellants and plastic prototypes. While it feels strategic to design a perfect war machine, it’s often far more practical to get a bunch of junky rockets together, pointing in roughly the same direction. I’m remind of the method used in The Three Body Problem where aerospace engineers launched a capsule (albeit unsuccessfully) into space by detonating a series of nukes. Sometimes, your destination is so far away that you cannot design a single engine that will persist through the voyage.

Same goes for cameras. The way you look at your problem or mission will change over time. I think some movements have failed because they lock in their worldview too early. Sometimes, this is the right way to go. But that kind of rigidity is not always durable. Over at SoP, for example, part of the project has been to evolve a definition of protocol over the course of several years. Indeed, the latest image of what a protocol is wasn’t in anyone’s list of candidate definitions when the program kicked off.

Default-disposable is not a typical approach, but it’s useful. Plus, it has tailwinds. I recently read Just-in Time Content by Aparna C, which aligns with the discussions we’ve been having in the Special Interest Group on Protocols for Business calls that I run every two weeks (info here).

As LLMs leak into some organizations and saturate others, there will be businesses that adapt quickly to the new technology. One way this is happening: teams of knowledge workers are drawing on flows instead of stocks.

“Recently, I used Microsoft 365’s Researcher to get the latest design decisions on an internal project. Instead of digging through old decks or asking colleagues for the latest updates, it assembled the most current information, tapping into chats, documents, and meeting summaries, into a single living brief.

It showed me what knowledge looks like when it’s drawn directly from flow, rather than hunted down from stockpiled artifacts.”

Just as copywriters made their work readable by search engines, businesses will increasingly make their operations legible to AIs. What you might lose in precision, you gain back in speed and creativity. Disposable cameras, in the form of LLM chat windows, are already an essential managerial tool in some places.

As Rafael put it in today’s SIGP4B working call, it’s now easier for a department head to generate an entire go-to-market strategy from scratch than it is for them to find the canonical version made by the business development team. While that strategy might contain hallucinations, it’s pareto sloptimal – now the biz dev team and the dep’t head are 80% of the way to being on the same page. For a fraction of the time cost.

I’ll close out with an analogy (another kind of disposable camera) and a provocation (a disposable engine).

Just-in time manufacturing revolutionized supply chains around the world. A mechanic shop today maintains only a few, shallow stockpiles. For one thing, the economics of just-in time inventories look good on balance sheets. Another, under-discussed factor is that inventories are difficult to maintain. It’s easier to just order the parts you need, when you need them, rather than organize an internal catalogue. Shops outsourced their inventories to suppliers.

White collar workers are facing a similar change in how their supply chains work. How much of the “inventory” of knowledge work can be outsourced? What happens when analysts draw on flows instead of stocks? And, more darkly, what is the Suez Canal blockage event in this new just-in time world?

Suez canal blockage options:

- Local power outrage that endures for a few days in SF

- South China Sea drama

- Solar activity

- New hit distraction gobbling up attention

What happens when analysts draw on flows instead of stocks? Hmmm one immediate result is that it can feel like a cacophony to management as there’s more and more information without new operational rhythms and culture, dare I say protocols, to find the signal in the noise. I see that today in my org where’s there’s a ton of legacy Taylorist managerialism in a this is water sense which leads to bandwidth blockages of executive time. Without delegation of basics, things languish so there’s a growing frustration as good ideas languish before execution, if it ever happens.

Good framing and quality 2x2

Nice. Reusable engines seems like a list of things that are risk of ossification, possibly cause they are built incrementally over decades rather than a couple of years? They also seem like things that have their own cosmotechnics depending on the region - such as Keynesian economics vs centralized planning economics etc or western legal systems vs islamic legal system.