Decision-Based Evidence-Making

Plus, a New Look for Blundercheck

“I like the red one.”

“Yep.”

“Everyone in agreement?”

“Alright, good. Red it is. Now, whose analyst is free to find some data to support this?”

Analyst don’t usually contribute to evidence-based decision-making. More often, they are a critical part of a decision-based evidence-making process. And that’s fine.

Data isn’t always used to make decisions. In fact, data is just as often the wrapping paper and the bow. It’s for faking it until you make it. Data is rhetoric. Organizations first choose, then retrofit their actions with evidence.

When people do this, we call it rationalizing or, more poetically, “making virtue out of necessity”. A period of time where action preceded reason. Typically it’s used in a derogatory way, like someone is dirty for acting without thinking. Same goes for me. Rationalizing and decision-based evidence-making used to (and sometimes still does) drive me a little crazy.

After I went from landscaper to analyst, I became privy to a lot of funding decisions. Projects ranged from a few thousand dollars to hundreds of millions. And the whole time I saw people make funding decisions, then scrounge for data to bulletproof their argument. That got to me. I was fresh out of biz school (still recovering) and was pedantic about rational decision-making.

Aren’t we supposed to make theories, then test them, then decide what to do? Isn’t our OODA loop screwed up? I thought Decide came after Observe? Didn’t our Vice President just say data-driven at the company all hands meeting? Why are we making evidence?

After seeing all this rationality theater, I discourage big data collection projects unless there truly is a testable, underlying hypothesis. That’s rare. Most people don’t frame a request for evidence as “find me a reason why we definitely shouldn’t buy the red one” even if that’s the logical path forward.

But – like I alluded to earlier – this isn’t always a bad thing. Consultants, greenhorn interns, and pop biz writers glamorize the idea of “scientific management”. In reality, people are just trying to get shit done. That means taking action even if you don’t have a clear idea of why you’re doing it. It’s what you do after that matters, including evidence-making.

If I had to offer my old self some professional advice I would say, “You’re not wrong. Evidence-making is suspect, but you’re also being a bit naïve because it’s not for the reasons you think. There are bigger issues here that need fixing first.”

Decision-based evidence-making is necessary under any of the following conditions:

Action is needed, there is no testable hypothesis, and you need buy-in from anxious stakeholders.

You are org-hacking to get around a roadblock, timeline, nemesis, etc.

You need to take action regardless, and the data you make creates a repeatable framework for future decisions.

First, we all have to make decisions without complete information. Of course, that’s a stress for stakeholders. More stakeholders means more evidence-making. Even with trust, you sometimes have to do just to keep people bought in to the process. Hence why you see a lot of decision-based evidence-making in large corporations and in the public sector. That said, such stakeholders are anxious due to information asymmetry. Keep in mind that finding some nice, confirmative data to calm nerves is a bit of a white lie. Don’t do it too much. Look for the sources of evidence that actually provide early signals and find a better way to explain the uncertainty under which you have to make decisions.

In the second case, either you are abusing a process or there’s something wrong with the process. Hacking is a sign that, probably, whatever your decision was off or the process isn’t functional. You might be in a Procrustean Bed or, worse, Procrustes himself. While occasional hacks might be called for, regular hacks means that it’s time for an audit.

Lastly, if you make evidence to rationalize a decision because you had to make a decision, whatever evidence you collect after the fact is an artifact of your philosophy. It reflects what you and your stakeholders consider facts about reality that are important enough to act on. A good question to ask might be: what were you stressing about?

The thing with decision-based evidence-making that I initially got wrong was that it’s totally fine…as long as you follow up appropriately.

Enactment

Organizational theorist Karl Weick has a hot take on this problem. Contra popular business star Simon Sinek’s Start With Why framework, Weick says teams converge on a shared how before they decide what they’ll do together, let alone agree upon why they do it.

I’m Team Weick 80% of the time, Team Sinek 20% of the time. More often than not, we choose what methods, techniques, and skills we need even before choosing what to do with them! And up until that choice, we have no rationale for our actions and therefore cannot make management decisions in a “scientific” way.

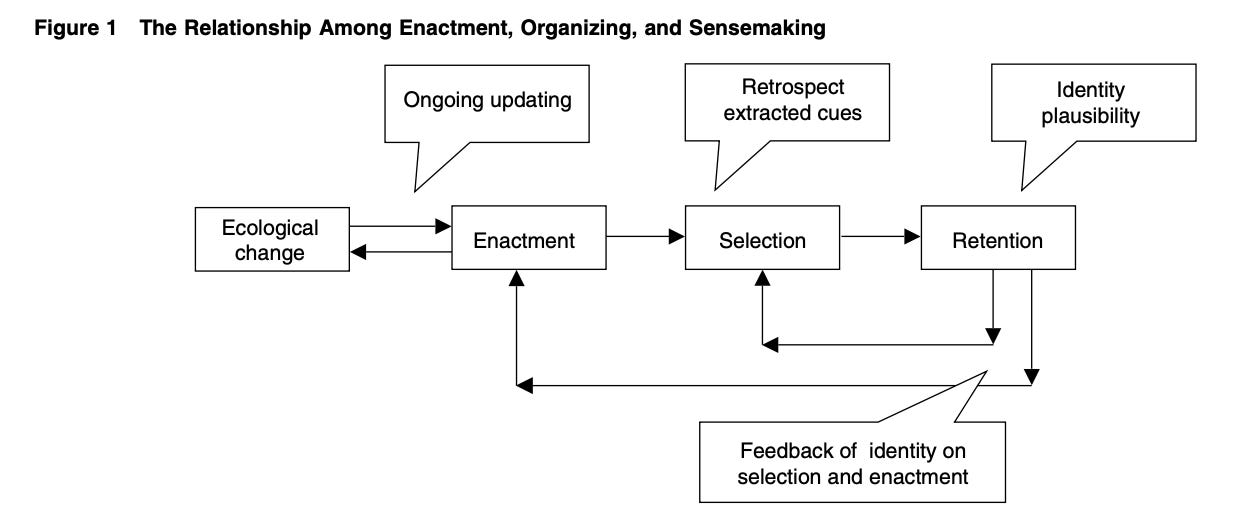

Lots of dense words in that diagram. At risk of oversimplifying: we don’t (at first) make decisions based on evidence. We respond to changes in the business environment, then analyze our action to make sense of those actions. That model of sensemaking then kicks off the rational loop of evidence-based decision-making that we value so much. At first, we flounder.

However, teams don’t close the loop. Evidence is made like single-use plastics. It creates temporary sense that’s thrown out because it was just a vehicle to appease stakeholders, trick oneself into action, trojan horse a project into an advantageous position, or respond to a rapidly changing business environment.

When I look back on my personal reactions to decision-based evidence-making (DBEM), it’s not surprising that the loop doesn’t get closed. We put evidence-based decision-making (EBDM) on a pedestal. Failing to meet that standard of rationality is kind of shameful, even if it’s an essential, unavoidable failure. Making it through a gauntlet of information-hungry stakeholders is daunting. Why would you get to the end and say, “Hey, guys, actually – that was mostly gut feel and it took us a while to figure out what cues we were paying attention to. Now that we know, can we can take note of those and continue to base our judgement on them moving forward?”

If you bullshit your stakeholders, that could look bad. If you intentionally game a funding process, could look really bad. But under the hood, that’s what needs to happen. It looks even worse to not get anything done at all. The road to EBDM is paved with DBEM.

Now 12% More Professional-Looking

Last week I updated the Blundercheck logo. I’ll miss the old knight. It was one of the first images I generated using Midjourney, which has been one of my most reliable tools this year. Super fun. While it didn’t turn me into Picasso, it helped me take on the job of interim resident artist for Protocolized.

This blog is about more than chess. It’s about business, safety, health, checklists, competition, tactics, long walks, and how to get better by making fewer mistakes. Hence I wanted a little bit more obvious of a logo – plus one that was less busy.

Sidebar: there’s something icky about strategists using the knight as a logo…stolen valor? From here on out you need to have a ELO of above 1800 to use a chess icon for your consulting business. In fact, if your organization is looking to hire a consultant and their website has a knight or rook as a favicon – a blitz match should be a mandatory component of the procurement process.

Anyway, here’s the latest iteration in glorious medium-resolution. It was rated as a 75% improvement by a focus group (my partner’s family’s aussiedoodle):

Appreciate all of you reading this blog – even if I still don’t really know why I write it.

Note: Summer of Protocols’ second annual symposium is from September 12 to 19. I’ll teach a module on protocol thinking. Free to attend, but since it’s part of a larger online course, space is limited and you should apply early.

I wish I could source the quote, "Most people make up their minds, then make up their reasons." Nice puzzle, btw. Found mate in 3.

Enjoyed this piece a lot.

I think the first time I heard the quip decision-based evidence-making it was Jonathan Korman in 2019, but I just found it again in the title of an MIT Sloan Management Review paper from 2010.

I think you nailed it. Those of us who gnashed our teeth against the failures of evidence-based decision-making fundamentally misunderstood how shit gets done, and fundamentally misunderstood how reality operates. For one thing, there's way too much evidence out there to go and collect it, if you did you wouldn't know what actually mattered amongst everything you'd collected anyway, and reality would've changed in the meantime anyway.

So you have to go and just do stuff. Ideally cheap, safe-to-fail stuff. Such action could be considered reckless DBEM because you're not trying to predict what's going to work, and you're doing work that might not work. But trying stuff is the only way to begin to understand the dynamics of the terrain, thus scaffolding even the possibility of EBDM.

I've started calling the operating approach you described "the double game", and I think innovation and research can only really happen when either you or someone up the chain from you is good at this game:

One game: you have no choice but to contend with uncertainty at some point, ideally by trying safe-to-fail probes and muddling through, frequently confused and thwarted. You must actively create conditions where the evidence can surprise you, leading you to stumble on much better ideas than you could've thought of beforehand. You must release your grip on future visions and let things unfold as they need.

The other game: you have no choice but to present a surface of confidence and progress to rivals, investors and others. You must tout confirmatory evidence and share no surprises, presenting the current best idea as if it were the plan all along. You must rally everyone around future visions and tell stories of how wonderful it's definitely going to be.

Or, simply:

"The deliberate strategy is what we present to the shareholders. The emergent strategy is what we actually do.” – a Japanese CFO quoted by J P Castlin

(Sinek's still a grifter tho)