The Voyage of Theseus

Requisite activity, lowercase aspirations, and corporate workshops

AI bros assault me on a regular basis. A deluge of grant money has made them religiously concerned about existential risk. So, when I share that safety is my primary research interest, they naturally switch into bible thumping mode. I bail, unceremoniously, as fast as I can. Even my thoroughly Canadian etiquette isn’t enough to stop me. Why? The hit rate on those conversations is just too low – at most, 1 in every 99 AI bros has a well-rounded conception of safety. We just end up talking past each other.

It all boils down to this:

Aerospace engineers don’t make safe planes. They design planes capable of making safe flights.

It’s a form of the Ship of Theseus paradox. Say you’ve booked flight AC 8472 to Montréal. While you’re at the airport, there’s an issue with the plane. Air Canada borrows a freshly maintained 747 from their friends at Air North, and swaps out the original plane. Different plane, same voyage. Some people don’t get it.

Some people do. In a brief conversation with Emmett Shear, he phrased it in a similar way – safety is built on top of an underlying layer of activity. That points to the underlying schism. There are two camps when it comes to safety. One traditional, one modern. Artificial intelligence, a cutting-edge field, is ironically steeped in antiquated ideas about risk and uncertainty.

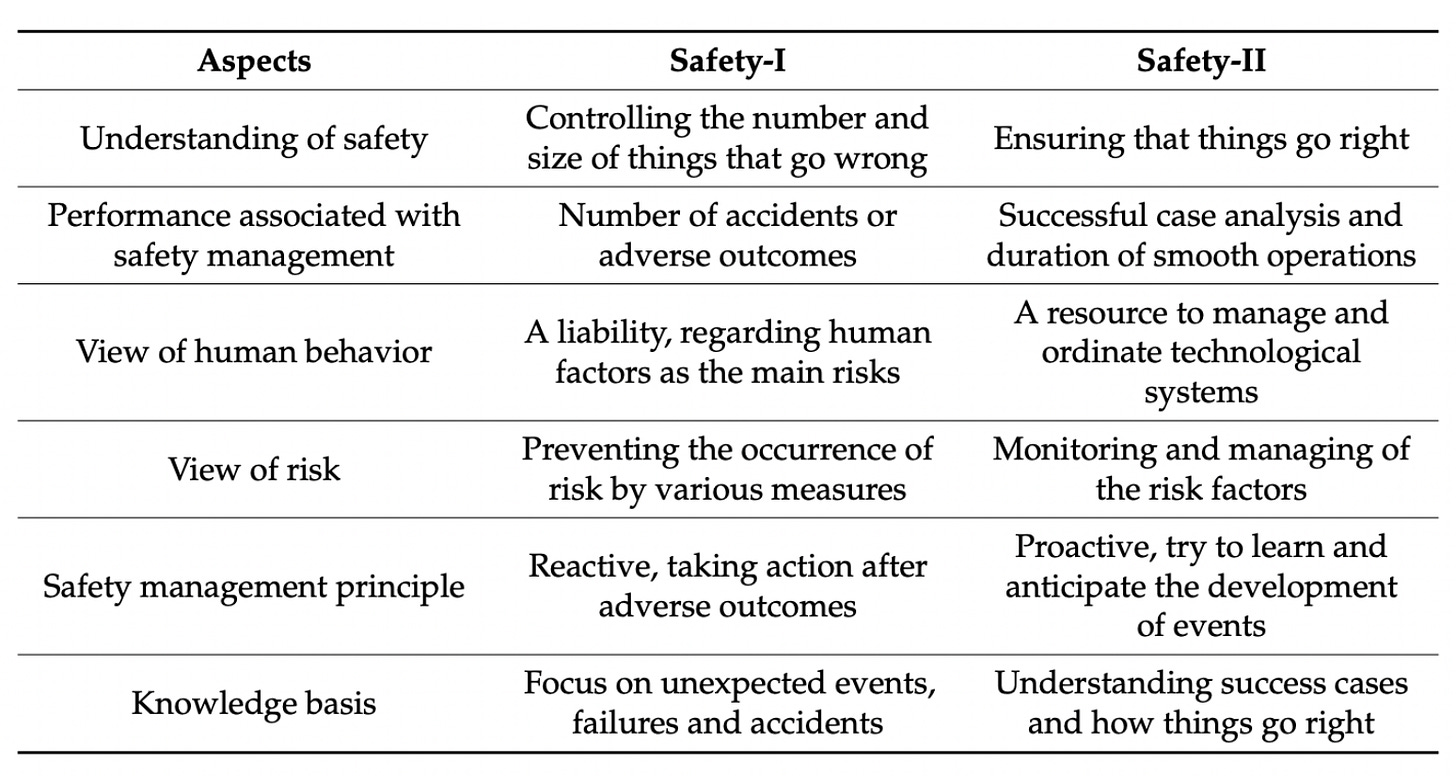

Erik Hollnagel defined two approaches to safety management:

That plane aphorism is a litmus test for whether or not someone understands the difference between Safety-I and Safety-II. There’s a time and a place for both. Naturally, if you view all risks and uncertainties in the same way, you have an incomplete picture. A strategy that minimizes a specific risk will also minimize any underlying activity, no matter how useful. Riding a bike to work has its hazards – telling your boss it’s too dangerous to commute at all might pose even worse problems.

The Voyage of Theseus also applies to cities, nations, and coordinated management of shared tensions. Last week, I was in Healdsburg, California for an event called Edge City. Really, it’s more than an event. Iterations of this same community have congregated in Denver, Aleph, Austin, Chiang Mai, and Cape Town – the epitome of a growing group of remote workers with a desire to travel. One way to think about it: there’s a flexible, holographic layer of digital communities that now periodically integrates with physical cities, create unique combinations.

And events like Edge Cities are called pop-up cities, not pop-up nations, for a reason. I think one of the reasons that the seasteading movement imploded is that it tried to create new nations. The aesthetics are great, but it’s a failed project.

Cities are more natural structures to interface with, even if they each sit within a nation. As Benjamin Barber pointed out in his 2012 talk, If Mayors Ruled the World, two cities in different nations often have more in common that two cities within the same nation-state; cities have lasted longer than states; “local government is where the rubber hits the road…”.

Cities participate in a web of activity that composes something more important than the individual cities themselves. Networks of remote professionals might have a lot to offer if they can unlock some innovative protocols that escape the problems of unsustainable tourism economies on the one hand, and isolated knowledge economies on the other. There’s a lot of opportunity there to bootstrap a form of bottom-up governance capable of navigating the today’s planet-scale problems that fall across many splintered borders.

Riffing on the plane safety idea – you can look at cities as their own thing, but also as vessels that execute a broader activity. A good city is a conduit for trade, ideas, technology, and more. Like planes are modules of an infrastructure that generates safe flights, cities network into a circuitboard that generates good life across the planet. Got a little woo there, but hopefully I made my point.

On a somewhat related note, I’ve been thinking about lowercase vs. uppercase goals. A typical brand playbook is to become uppercase – a household name, like Kleenex or Ferrari, is synonymous with the category (tissue paper / supercars) it serves. Most businesses, consultants, and writers aspire to be uppercase. That’s as much a matter of being able to capture value latter as it is about ego. A wrong-footed desire to create a Something that hamstrings so many projects that are fundamentally lowercase.

If you are trying to change the way people think…or behave…or organize, you want to be lowercase. Uppercase movements are contingent on the reputation of an idol or brand. A successful lowercase strategy should avoid definitions and titles and labels for as long as possible. Take a failed case – many proponents of AI safety run into an uppercase trap. A single, aligned artificial intelligence is more brandable than a plurality of AI agents that safely perform countless operations.

Aspiring lowercase sounds like an oxymoron, but it’s not. It merely acknowledges that a centralized reputation creates a degree of fragility that some projects can’t afford. Many projects can, and should, aspire to be Uppercase. There’s no right answer – nor are these things (like safety-i and safety-ii) mutually exclusive – it’s just a contour of the landscape that you should consider.

Brands are uppercase, vibes are lowercase. Manifestos are uppercase, practices are lowercase. Elections are uppercase, movements are lowercase. Slogans are uppercase, stories are lowercase. Public relations are uppercase, partnerships are lowercase. Nations are uppercase, cities are lowercase. Planes are uppercase, safety is lowercase. Ships of Theseus are uppercase, voyages of theseus are lowercase.

P.S. Two weeks ago, I ran a workshop with MWD, the largest supplier of treated water in the United States. I’ve been developing a model based on spannungsfelds and tensions. In Montréal, Whitehorse, Victoria, Vancouver, Seattle, or Portland? Grappling with a tough problem space? I’ll be on the road from July to October and have some pro bono consulting capacity – happy to explore ideas over email.

Would this (Apollo 13) be a case that spanned all three silos of Hollnagel's Safety Trifecta?:

https://medium.com/@moin.ekvg/creativity-under-pressure-a-successful-failure-e77bdf417a19

Oh! I see why now hehe #protocolized