The Three Types of Space

A Guide to Returner Protocols

Once upon a time, there used to be one type of space. Now, there are three. Not all spaces are created equal – and knowing the difference makes a difference.

Today’s blog is about a set of protocols that reliably improve operations. Ones like put things back where you got them or leave things a little better than you found them. I like to call these returner protocols. And, because we often don’t make the most use out of our precious spaces, even little tweaks can improve quality, safety, productivity, reliability, resource utilization, speed. You just need people to be effective returners. But most people aren’t – which is why it’s an effective lever to pull on.

Any hub of operation is in a constant battle with entropy. Your kitchen. Your muscles. A distribution center. A sign-making business. Your local library. And if you take a look around at the high-performance hubs, you’ll notice that:

Everything has a place.

If a thing does not have a place, it will be assigned one.

Occasionally a thing gets promoted or demoted to a new space.

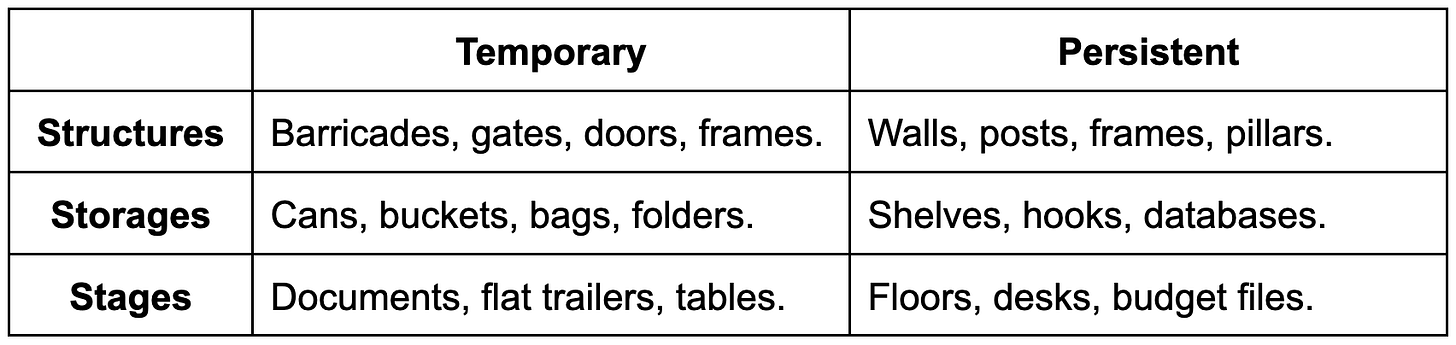

There are three types of spaces: structures, storages, and stages.

It takes a team to get things done. And until Elon Musk delivers on his promises of a device that links our neurons together, being on a team means a messy, frankenstein memory about where tools are kept, who is supposed to tidy up, which mechanic touched the visegrips last, etc.1 It also means witch hunts for missing parts, manuals, books, receipts, passwords, data… and tripping on shit that people left out (or that you did).

Working together is essential and difficult.

The library reshelving cart is a classic instantiation of a returner protocol. In a maximally thorough world, everyone would understand the Dewey Decimal System used for library organization. In practice, that’s unreasonable. There are folks who get PhDs in library science. It’s too much to ask, so librarians and their clients meet in the middle with the mobile shelf.

That’s an evolved example, but it’s a second layer to the original kernel. Put the thing back where you found it. If you don’t know where it goes, or aren’t sure, put it somewhere highly visible to those who know where it goes.

This brings us nicely to the three types of places in an operating center. There are actually six unique types, since each of the main types (structures, storages, and stages) has a binary qualifier:

Getting your space-types messed up will get your operations messed up. Cluttered stages are inefficient and can be dangerous. Temporary storages that become persistent are usually not durable enough, and increase maintenance burdens quite a lot. Structures, both temporary and persistent, are typically harder to change but provide a lot of potential if used intelligently.

The first step here is accurate classification of the types of spaces in your operating area. For example, I have a 2016 Outback2 that my partner and I are on track to drive 30,000 kilometers this year. The frame, trim, body panels – those are all structures. The rear seats and hatch cover are also structures, but because they’re temporary ones. We have cupholders, a glovebox, and a roof rack (persistent storage spaces) as well as a couple of milk crates and a roof box (temporary storage spaces). Lastly, there are stages. The floor of the hatch functions as a place for various activities, from packing bags to making a cup of coffee. It’s a persistent stage, but sometimes gets cluttered by stuff and becomes a de facto storage space. And that’s the crux of the issue.

It’s very easy to lose one kind of space to another. The main way this happens is transient objects that clutter stages or consume valuable storages. That is exactly why it’s so strangely effective to put stuff back. It clears avenues for productive activity to emerge without immediate loss of momentum.

Stages are where activity happens. Activity is what creates products, services, art, and, of course, accidents. Stages need to be kept clear and organized, so actors can use them efficiently. For example, sign-making shops (good ones) are super tidy. Not only are storages organized sensibly, with frequently used assets closer to stages, but stages are kept clear. Walkways, work benches, desks, parking lots, doorways, reception areas – these are not storage.

It’s not that they should never be used as storage, but that their default state is that of a stage for the choreography of work.

Structures are another interesting case. On their own, they’re somewhat wasteful. Of course walls and poles and beams maintain the integrity of our offices and warehouses, but they do take up room. It’s a smart idea to have these things serve multiple purposes. Can we put hooks on that wall? A whiteboard? Could we route our queue around that pillar to make the experience of waiting in line a bit more interesting? What if we put a mural on it? Or a dope ass 360º bar?

Now that you have a better sense of the spaces in your operating area, what do you do?

That depends on how many people there are and how many objects there are around. The more people and objects, the more you need a replacer protocol. Tools and props without homes are a real killer (sometimes literally). And the more people using a stage, the more important it is to reset it frequently.

The simplest way to bootstrap into better space management: create a return cart. Help out your warehouse librarian by creating a depot for the tools. Or, take on the role yourself. If you’re concerned that your colleagues’ brains will atrophy as a result – don’t. As you return things to their rightful home, people will know to find them there. Then they won’t have an excuse not to put them back!

"It's lovely to be useful." - Jony Ive

I’ll end with a caveat rather than a mic drop. It’s not always the case that you should be intensely tidy. Overly sanitary gardeners and obsessively compulsive foresters have a horrible track record. There’s a certain degree of complexity in some projects that’s impossible to remove. Sometimes your best bet is to irrigate areas with resources and attention, rather than orchestrate the scene with harsh protocols.

Plus, sometimes these systems fail. And that’s alright. When this one does, just bring back the returner cart and take the opportunity to find better places for things. Be liberal in the time you spend returning things. Be conservative in the time you save leaving things out.

Returner protocols will be something I dive into during the short course I’ll teach at this year’s Protocol School. Deadline is tomorrow, August 22!

Those with a DIY-loving parent will probably have experience with this. Where the f&$k did Bobby put that allen key!?

It’s a 3.6r, in case you were wondering (probably not). 😎

I used to be all about return protocols until I got married. My ADHD wife has an entirely different “everything should be left wherever you last used it, and there are only stages” anti-protocol that has the 2nd law on its side, so it’s now been 20 years of tension between her taking stuff out of cabinets when they catch her eye and spark an impulse (“ooh cake pan, I’ll bake a cake!”) and leaving them around and me putting them back (at which point she considers them “lost” and needs me to find them again). If I ever organize her visible chaos for her, she just fills up the newly cleared staging spaces with more shopping. As far as she’s concerned there are no storages and structures in the universe. It’s all stages. Out of sight = blinks out of existence.

Shows up in inbox style too. Her email is 100% in inbox, literally 1000s. Mine valiantly striving for inbox zero all the time and hovers between 30 to 300 these days.

Given it’s an uphill battle on my end, I’d say I’ve mostly given up.