You Believe What You Eat

On the Evolution and Trajectory of Dietary Tribalism

The best predictor of someone’s ideology is their diet.

Imagine two maps of the contiguous United States of America. One map color codes states by Republican and Democrat leanings. The other shows which states prefer Keto and which prefer Vegan. They line up almost perfectly.

Obviously, ideology is upstream of diet in terms of causality. Religions issue strict food preparation protocols. Eating a pork chop with applesauce won’t make you believe in God.

Wrong… I fell into that trap a while ago.

Narrative Food Wrappers

It’s diets that spark religious beliefs. And eating a pork chop can make you believe in God. This is why we had – and still have – such brutal dietary tribalism. We’re past the peak, but the feud between Seed Oil Bros and Plant-Based Bros isn’t over.

There are a few ways this can happen and one is particularly common. It starts with Bob, who wants to lose a couple of pounds or get a six-pack to impress girls (actually, it’s only his buddies that will care). In order to do that, he needs to get into a negative energy balance. Calories in minus calories out, so a CICO of less than 0.

To be a bit more precise (and to make it clear that I’m not completely bullshitting on this topic) here’s how energy balance is calculated:

Caloric Intake - BMR - NEAT - TEF - Exercise = 𝚫 Energy

Caloric intake is what you eat. Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) is how many calories you burn at rest / to stay alive and alert. Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) includes things like when you nervously bounce your knee or pick your nose. Thermic Effect of Food (TEF) accounts for the calories burned by the digestion of some foods, like insoluble fibre.

BMR, NEAT, TEF, and plain old exercise add up to your caloric expenditure – “calories out” of the metabolic system.

It’s not realistic for Bob to increase his BMR, NEAT, or TEF to lose weight. They’re either genetically determined or too marginal to matter. His only options are to reduce caloric intake or exercise more. Bob is busy and going on a diet is less time-consuming than exercising more.

Blundercheck: when faced with the choice between eating less or exercising more, choose exercising more.

But who’s selling the diet that tells you to eat the same stuff, just 20% less? No one. Despite accomplishing the same thing—a CICO of less than 0—every diet has a unique ideological wrapper that makes it easier to adhere to.

Keto: Reduces caloric intake by restricting the intake of carbohydrates. Story – carbohydrates are ruining your metabolism.

Vegan: Reduces caloric intake by restricting the intake of animal products. Story – we evolved only to eat plants.

Christian Orthodox: Reduces caloric intake via date-based limits on the intake of fish, dairy, and red meat. Story – something about gluttony.

Paleo: Reduces caloric intake by elimating non-“ancestral” foods. Story – our digestive systems have not kept up with changes in food.

Slow Carb: Eliminates refined carbohydrates. Story – fast carbs don’t satiate your appetite and are designed to get you to eat more.

Peat: Eliminates most vegetables, nuts, and seed oils. Story – some BS about supercharging your metabolism.

Whole 30: Restricts diet to combinations of 30 base ingredients.

Atkins: Basically Keto.

So and so forth…

Whether or not these diets are effective depends a lot on the individual. But one thing is consistent: adherence requires buying into the narrative of the diet. For example, it’s much more potent to say that seed oils are inflammatory peasant food than to be like aw, geez, I should probably cut back a bit on french fries. Not only that, but blaming some sort of industrial complex, conspiracy, or macro-level trend is an antidote to guilt.

I should know. Unlike most people, I have tried most of these diets – from carnivore to vegan. Indeed, few others have as much claim to being a centrist as I do, having journeyed to both ends of the horseshoe and back.

In some ways, I have a natural defense against dietary tribalism: my severe allergy to peanuts, cashews, lentils, chickpeas, and all other sorts of legumes and tree nuts. Because I was, effectively, born with an preassigned elimination diet, I’ve had no trouble staying lean.

Obviously that defense wasn’t enough. Like most lads with a partially developed prefrontal cortex, I really wanted to get jacked. It was no contest. I went down the dietary rabbit hole from the opposite direction. I needed to get to a CICO balance of greater than 0.

That led me to buying into this whole weird narrative of different body types: ectomorphs, mesomorphs, and endomorphs. As if humans spawn in three distinct phenotypes… anyway. I self-identified as an ectomorph (who have trouble gaining weight). Miraculously, after consuming a disgusting amount of protein powder, oatmeal, and eggs, I finally managed to put on some pounds.

Satisfied with that, it was time to get lean again, and after another 30-second search for a suitable regimen I encountered the concept of a paleo diet. The narrative was simple: we have evolved over millennia, but our food systems have completely changed in the course of a couple centuries.

It was terribly appealing to me. The idea that I would not only get more ripped, but that I would also solve my allergies AND sound erudite while doing so? Hard to say no to that. By buying into the narrative, it was easy to stick to the diet. In fact, it hardly felt like a diet. More like a belief system.

I did wind up in pretty good shape. Physically and energetically, I felt better.

But I also became frustrated with things far beyond my circle of control. Big agriculture. Glacial action against Covid-19. Seed oils. Cultural feuds. The food pyramid. Unions. Things that I had rarely even thought about before, yet alone had strong opinions about. Through my self-indulgent search for content that would entertain these frustrations I found a lot of folks who felt the same way as me. No surprise, they also ate same way as me.

It’s not coincidence that the narratives that explain and enforce the paleo diet lead to such conclusions about life today – that its features are effectively alien to us, because they emerged so quickly and humans evolved independently of them. It’s a valid argument, but also horribly myopic. There’s more to life than what you eat and little reason to think that the logic of what food to eat should extend to political matters. Although, as I will explain later, there are some parallels.

There was a deep irony to the paleo and paleo-adjacent crowd’s obsession with ancient Greek and Roman civilizations. Those people consumed a lot of bread and grains. Including the especially jacked gladiatorial class.

The fact is, diets do work. Many of us do experience physical and metabolic benefits from adjusting our caloric intake relative to our activity level. However, there’s a colossal heap of BS out there, which is easily picked up and sold by health influencers with something to sell. Unfortunately they’re pretty good marketers – in the Grabowskian sense that they’re able to make new customers with effective narratives. Narratives that are the roots of dietary tribalism.

The Origins of Dietary Tribalism

Our zeal for diets that are Trojan Horses with ideological payloads isn’t a new phenomenon at all – it has deep roots. Many ancient societies codified food rules as divine commandments or cultural taboos, complete with myths and moral rationales. Again, it was food first, faith second.

These protocols often had practical benefits for health or survival and were, notably, enforced through the powerful glue of belief. People did not need to understand the underlying microbiological mechanisms in order to benefit. In essence, diets had religions. Eating (or not eating) certain foods could indeed make you a believer – or at least a more cohesive community member.

Consider one of the oldest and most pervasive examples: religious dietary laws. Judaism’s kosher rules and Islam’s halal code include similar prohibitions – for example, the complete avoidance of pork.

On the surface, these are framed as matters of ritual purity or religious orthodoxy. But there are practical reasons below. Pigs were difficult to raise in hot, arid Middle Eastern climates and often carried parasites and disease. Marvin Harris and others argued that the taboo against pork had a utilitarian origin: in a region short on water and grazing land, pigs competed with humans for resources and harbored Trichinella worms and other pathogens.

Avoiding pork would have improved a community’s health outcomes (fewer parasitic infections) and conserved resources – even if ancient Israelites or Arabs didn’t know about microscopic parasites, they knew pigs made people sick and were costly to feed. Thus, “unclean” swine became religiously off-limits – edict of a diet, bolstered by sacred narrative. The practical effect was a healthier, more resilient population.

Many food taboos around the world show this blend of medical/ecological insight and spiritual enforcement. Traditional kosher law mandates specific slaughter methods (draining blood) and rejects any animals found already dead (carrion). These rules sound like unthinking traditionalism, but they align with food safety – ensuring meat is fresh and free from blood-borne illness.

In tropical regions, cultures often tabooed eating certain carnivorous fish or bottom-feeders, which we now know tend to accumulate toxins. Snakes or other venomous animals are shunned as food in traditional lore – unsurprisingly, since the risk of catching and consuming them often outweighs the nutritional benefit.

A Hindu example: strict Hindus refrain from eating after sunset and traditionally avoid harvesting fruits at night, a practice born in an era before artificial lighting when groping around in the dark for food meant more snake bites and injuries. In all these cases, what might have started as sensible precautions became wrapped in ritual. By obeying the taboo, people reaped health benefits, and by cloaking it in spiritual terms, the community ensured prosocial compliance.

When a whole tribe agrees that only food prepared a certain way is acceptable, it means you naturally eat mainly with your tribe. This limits commensality (shared meals) with outsiders, which in turn preserves cultural cohesion. As one research review on food taboos notes:

“…any food taboo, acknowledged by a particular group of people as part of its ways, aids in the cohesion of this group, helps that particular group maintain its identity in the face of others, and therefore creates a feeling of ‘belonging’.”

Even arbitrary or extreme food taboos carry a kernel of ancient trial-and-error wisdom. In some Pacific Island tribes, only the chief’s family could eat a certain delicacy like a large fish or wild pig. Selfish? Perhaps – but it limited depletion of a resource by the whole population. And if you broke these rules, it was a sin, punishable not only by the community but by the spirits or gods.

In these ways, food and faith intertwined to guide behavior. Diets are defended with a violent fervor. Indeed, history is rife with examples of brutal dietary tribalism. In medieval Spain, inquisitors famously checked whether converts from Judaism were secretly still keeping kosher – something as simple as refusing pork could arouse deadly suspicion. That’s how defining these diet identities were.

And this was the origin of dietary tribalism: shared beliefs about food that confer both survival advantages and a sense of “us vs them.” It’s a pattern that continues today in new guises. A Paleo dieter railing against “industrial grain subsidies” or a Vegan condemning meat as “violence against animals” are, in a way, echoing priests and prophets – wrapping what might be sound nutritional advice (eat more whole foods; eat more plants) in a grand narrative of good and evil.

The big difference is that now, ideology has been replaced (at least in theory) by secular science and policy. And that brings us to the next phase in the evolution of how we eat: the secularization of diets.

The (Mostly) Successful Secularization of Diets

From the 1800s to late 1900s, humanity’s relationship with food transformed. In much of the world – particularly the West – the old religious food laws began to lose their grip on daily life. Nation-states and scientific institutions stepped had begun the secularization of dietary guidance.

Instead of priests or village elders telling us what to eat (and what it means symbolically), we got doctors, nutritionists, and government agencies issuing guidelines.

“Thou shalt not eat pork” evolved into “For a healthy heart, limit saturated fat to under 10% of calories.” The language changed from moral to medical.

How successful was this secularization? Massively. While heart disease is still a leading cause of death, new protocols launched by scientific institutions reduced many other ills, like goiter, rickets, pellagra, and neural tube defects. Nutrition research and development saved millions of lives. However, as we see today, it also set the stage for new conflicts and tribalism, just with new high priests (or influencers) and new heresies.

The rise of nutrition science changed everything. For the first time, researchers identified vitamins and minerals and traced specific diseases to their deficiency. This new knowledge quickly translated into public health action. Governments began intervening in the food supply in a very practical (and entirely religion-neutral) way: fortifying foods with essential nutrients.

Fortification

To illustrate how effective this was, here are a few landmark achievements:

Salt Iodization (1920s): Starting in 1924, common table salt was fortified with iodine to prevent goiter – a thyroid disease that was rampant in inland areas due to iodine-poor soil. Iodine deficiency disorders vanished in countries that adopted iodized salt. The swollen thyroid glands of the “goiter belt” in the Great Lakes region of the US became a rarity. No religious edict necessary.

Milk Vitamin D Fortification (1930s–40s): Rickets, a crippling bone disease in children, was found to be caused by vitamin D deficiency. The solution was simple: add vitamin D to milk. By the 1940s, rickets went from ubiquitous to uncommon in America and Europe. No ceremony.

Enriched Flour and Bread (1940s): In the early 20th century, pellagra (caused by niacin deficiency) was killing tens of thousands in the American South. Joseph Goldberger famously showed it was a dietary issue, not an infection, despite facing ridicule. Once niacin, along with thiamin, riboflavin, and iron, were mandated to be added to flour (War Order No. 1 in 1941 and US standards soon after), pellagra virtually disappeared by the 1950s. No taboos.

Folic Acid in Grains (1990s): Scientists realized that folate deficiency in early pregnancy led to neural tube defects in newborns. Rather than implore would-be mothers to eat liver or lentils (rich in folate) the U.S. FDA decided in 1996 to require folic acid fortification in cereal grains. This took effect by 1998. The result: a significant reduction in birth defects like spina bifida in the following decades.

Four cases where a secular fix achieved what no amount of individual sermons or tribal fervor could. Three even reached everyone through their daily bread!

These examples highlight a key aspect of secular diet interventions: they tend to be universal and inclusive. Unlike a religious rule which might apply only to believers (and exclude or even ostracize others), a public health measure like iodized salt or enriched flour quietly benefits anyone who eats. Nutrition became a field of statecraft and scientific progress.

Dietary Guidelines

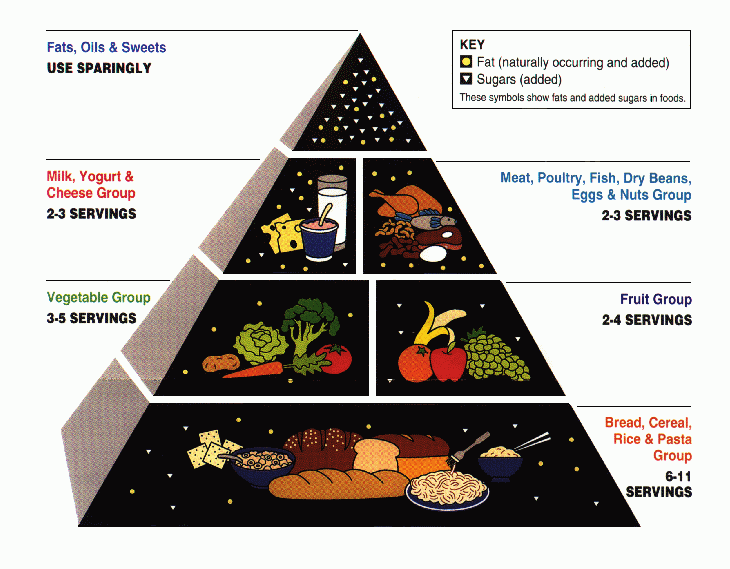

Alongside fortification came public dietary guidelines – essentially a secular gospel of eating. The United States pioneered this with the USDA’s food guides.

That pyramid (see image above) neatly stacked food groups with breads and grains at the base (to be eaten in greatest quantity) and fats and sweets at the tiny apex (to be used sparingly). This was essentially a visual codification of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which had begun in 1980 and were updated every 5 years. It was secular and intended for everyone, from any background – a stark contrast to, say, kosher laws that concerned only Jews or halal only Muslims. Here was one diet to rule them all, based on the best nutritional science of the day.

Of course, no single diagram could capture the complexity of nutrition science, and the Food Pyramid was not without flaws or critics. For one, it lumped all fats together at the top as “bad” and all carbs at the bottom as “good,” which we now recognize was an oversimplification (avocados and olive oil are far healthier than white bread, yet the pyramid’s design might suggest the opposite). Furthermore, the pyramid’s high-carb base was later blamed for inadvertently promoting refined starches – some argue it contributed to the 1990s boom in processed low-fat, high-sugar foods, as people swapped butter for Snackwell’s cookies. There were also accusations of industry influence: lobbyists from the dairy, meat, and grain industries certainly had input in shaping the guidelines. The result – a fairly carb-heavy, dairy-heavy pyramid – conveniently aligned with agricultural subsidies and food company interests, critics noted.

Yet, even with those caveats, the secularization of diet largely succeeded. By the 1980s, virtually no one in developed countries was dying of scurvy or beriberi anymore. Instead, the focus turned to metabolic syndromes – heart disease, diabetes, hypertension.

Here too, broad diet recommendations and public education made an impact. It wasn’t all due to diet – better medical treatments helped – but diets low in sat fat were part of the public health strategy, and they did coincide with improved cardiovascular outcomes

Nutrition Facts

One of the most powerful tools of diet secularization was the introduction of the Nutrition Facts label on packaged foods. This came about in the 1990 Nutrition Labeling and Education Act, with labels becoming mandatory on most packaged foods by 1994.

For the first time, a consumer could just flip a box and see a standardized panel telling them calories, grams of fat, protein, carbs, and percentages of daily vitamin needs. It’s hard to overstate how transformative this was. The symbolic implications are huge: it essentially secularized and democratized the knowledge of what we’re eating.

Instead of trusting a butcher’s word that the meat is “clean” per religious law, you could trust that it was inspected by the USDA and then decide for yourself if the fat content was within your personal health goals. The label became a kind of secular scripture, universally recognized – that black-and-white table is now on products in over 50 countries (with variations).

And it keeps evolving with science: in 2006, trans fat got its own line on the U.S. Nutrition Facts label, which led many companies to eliminate hydrogenated oils rather than have the dreaded number on their packages. More recently, “Added Sugars” earned a line, reflecting concern over excess sugar consumption. All of this is about giving people information and letting them make choices according to secular health principles.

Allergen Management Protocols

A final aspect of this history is how we handle food allergens and intolerances. In the past, if you were allergic to, say, peanuts or shellfish, it was just your tough luck and you navigated at your own peril, often relying on personal vigilance and social kindness.

Today, it’s a matter of policy and law. Packaged foods in the U.S., EU, and many other countries must clearly indicate if they contain any of the major allergens – for example, a label will say “Contains: milk, soy, and wheat” in bold letters if those are ingredients. This became law in the U.S. with the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 (effective 2006).

As someone with severe allergies myself, this regime of labeling is a lifesaver. I don’t have to stick to some traditional diet to stay safe; the whole food industry accommodates my needs (to a reasonable extent) by informing me what’s in the food. Of course, we should be more diligent with exposure therapy (things like the LEAP protocol) in order to reduce population-level rates of allergies, but labels are important too.

All these developments – fortification, guidelines, labeling, allergen policies – represent a secularization of diets in the sense that they apply to everyone and are justified by reference to universal human health and scientific evidence. Notably, they are relatively narrative-free. You don’t see government pamphlets saying “Eat whole grains because that’s what our ancestors intended” or “avoid trans fats or you’ll anger the gods.”

Instead you see reasoning like “whole grains may reduce the risk of heart disease” or “trans fats increase bad cholesterol and heart attack risk”. It’s rational, factual, and inclusive.

Importantly, secularization also means pluralism. A government can recommend an ideal diet, but unlike a theocracy, it won’t typically enforce it by law (except in specific contexts like school lunches or banning truly harmful substances). People remain free to follow their eating patterns – vegan, keto, halal, kosher, gluten-free, you name it – as long as they don’t harm others.

Yet this hasn’t eliminated dietary tribalism – it has merely changed its form.

When the U.S. government put out the Food Pyramid, it inadvertently unified a coalition of critics ranging from Atkins diet devotees to paleo enthusiasts who would later rail against that pyramid as “the grain-heavy, insulin-spiking nonsense that made America fat.” The backlash against official dietary guidelines has been fervent in some circles.

In the 2010s, we saw open conflict between the low-carb tribe and the low-fat tribe, each citing dueling studies as scripture. Online communities formed around eating philosophies (from raw vegans to carnivores), many of which defined themselves in opposition to the “mainstream” nutrition narrative. Horseshoe theory of nutrition, anyone?

There’s another layer to this analogy of diet and ideology – one that goes beyond individuals and even cultural groups. What happens when we apply the concept of diet to entire nations or civilizations? Just as a person or a religion can have a guiding diet, so can a country or an economy.

In fact, today’s global conflicts over climate and energy can be seen as a form of dietary tribalism at the planetary level: a clash of “metabolic regimes.” Are we, as a civilization, going to stick to our fossil fuel diet, or switch to a renewable energy diet? And what narratives are springing up around those choices? Let’s zoom out to that macro scale.

Zooming Out: Metabolic Stacks and their Narratives Apparatuses

What if we viewed a country’s economy as an organism with a diet? In a sense, nations “eat” resources to survive – they consume energy, minerals, and food to fuel their growth, just as we consume calories to fuel our bodies.

This is a tested analogy. Economic historians and political scientists increasingly use terms like “metabolic rift”, “energy regime”, or as historian Nils Gilman puts it, the “metabolic basis of modern industrial society.” They argue that much of geopolitics and ideology comes down to the question: What is your society’s primary energy source and consumption pattern? What’s your macro-level diet?

I only have a little bit to add to this discourse, since many others are taking it on. Right now, the world is experiencing a profound conflict that mirrors patterns of dietary tribalism and its origins in narrative-wrapped protocols. A nation’s choice of diet has obvious implications for its dominant ideology.

On one side, we have regions shifting to a new diet of renewable, clean energy – solar, wind, hydro, etc. On the other side, we have those clinging to the old diet of fossil fuels – coal, oil, natural gas.

It’s almost as if we have vegans vs. carnivores again, but this time at the level of nation-states and with the planet’s future at stake. Let’s outline the two main dietary blocs in this global bifurcation. What’s remarkable is how each side tells a story that gives meaning to its diet:

Green Energy

Net importers of fossil fuels and have strong incentives to kick the habit.

They are investing heavily in renewables and framing it as the path to prosperity and survival.

The European Union and China stand out here. Europe, lacking abundant domestic oil and gas, sees transitioning to wind, solar, and other renewables as not only environmentally responsible but crucial for energy independence (for example, after experiencing the geopolitical blackmail of relying on Russian natural gas.

China is positioning itself as the leader of a new green metabolic order – not because its government woke up one day as environmentalists, but because renewables offer a form of energy that China can produce domestically (sunshine and wind are sovereign resources) and thus reduce reliance on foreign oil.

Chinese leaders openly talk about becoming an “ecological civilization” and are exporting solar panels and high-speed rail the way the US once exported oil derricks and gas-guzzling cars. Europe and China, though very different politically, share these “metabolic interests” in shifting energy sources.

Their narrative: “The future is clean and electric. We will modernize and save the planet at the same time.” It’s a narrative of progress, innovation, and also, subtly, of liberation – liberation from the geopolitics of oil and gas. For Europe, green energy means not bowing to Moscow or Riyadh for fuel; for China, it means wielding the keys to the next energy era.

Fossil Fuel:

In the other corner, we have nations whose economies (and often political structures) are deeply tied to coal, oil, and gas extraction.

These include the obvious petro-states like Saudi Arabia and Russia, but also the United States – at least under certain leadership.

Their narrative is one of tradition, sovereignty, and in some cases denial. Take the U.S. under the Trump administration: it rolled back renewable energy supports and loudly promoted coal, oil, and gas as the backbone of American greatness. This was more than economic policy; it became a cultural narrative – a kind of crude populism (ba dum tss).

Fossil fuels are cast as symbols of national strength and self-reliance. Environmentalism was recast as the creed of meddling globalists or effete urbanites, out of touch with the heartland where real men dig oil wells and coal.

Saudi Arabia and Russia also couch their fossil fuel focus in nationalist terms: it’s the source of their geopolitical power, and any move to cut emissions is seen as a direct threat to their way of life.

The renewables diet narrative is about innovation, moral responsibility, and the promise of a cleaner, egalitarian future. The fossil fuels diet narrative is about heritage, strength, and skepticism of change. These narratives often borrow language from older ideological struggles and, similar to those wrapping contemporary diet fads, are an almost subconscious apparatus to enforce adherence.

For a moment, forget the content of these macro-level diet-narrative pairs and just look at their structure: each side in the energy war sees itself as good and the other as bad – classic tribal thinking. One side sees petroleum consumers as reckless destroyers of our common home; gluttonous runaway consumers. The other side sees green proponents as utopian tyrants, trying to force a new ascetic diet on the world that will rob people of jobs, comfort, and tradition.

These mirror the moral tones we find in personal diet debates. It’s the same dynamic, zoomed out to industries and carbon emissions.

Where does this go? Well, just as we’ve seen with the secularization of personal nutrition guidance, there has been progress in defining universal standards for maintaining a healthy planetary metabolism. Carbon accounting is a step in that direction, for example. Of course we’ve also seen a corollary in the backlash: secularization didn’t defeat dietary tribalism (petroleum vs. renewables) but permanently changed the dynamic. We’re in the late middlegame of regions choosing diets and opting into the supporting ideology.

It’s tough, but I’m optimistic. Things are very noisy today in the nutrition world but there continue to be major improvements in technology, medicine, and monitoring. I still think we need a better open-source standard for wearables and personal health data, but overall we’re trending in the right direction. With parallel improvements in how we approach measuring planetary functions, maybe we’ll get towards a functionally better place (even if the ends of the horseshoe remain intensely tribal).

More on Metabolism

First of all, read Small Precautions (macro) and Marco Altini (micro) for more sophisticated takes on this at different scales. If you want a more mesolomaniac view of things, there are a few recent Blundercheck articles worth checking out:

How interesting to be Chinese, then, where traditionally/culturally nothing is off-limits (not referring to Chinese people who profess religions with dietary restrictions), and where food is medicine and vice versa. In fact, TCM guidelines about diet (heaty vs cooling foods, etc.) can be seen as a kind of protocol.

On an integrative note have you checked out strength side? I feel you'd dig