Safety at the End of History

A Moment of Post-Bear Appreciation

In honor of 500 subscribers I will now share 500 of my best safety tips… just kidding. But seriously, thanks for reading. Super cool. In exchange, a story…

Five days ago I ran into a grizzly bear. He was a cub, but still weighed at least 200lbs, and was miserably cranky. Fair enough. It was 5:15 in the morning.

Normally bears look at people then carry on with their day. This time, the bear started growling and zigzagged towards me. To make matters worse, his mom (~350lbs) was also nearby, with three other cubs. Total death engine weight: ~1150lbs.

It’s been a while since I was worried a bear would take a run at me, let alone two, but this was one of those times I was worried about it. Our car was about 500 feet behind us.

After a long walk backwards in Birkenstocks with a hand on the bear spray, we made it to the car. Brother bear came right up to say hello (might have been saying “screw off”, I don’t know, I don’t speak bear).

If you’re familiar with some of my research you might be thinking… safety guy rubbing shoulders with an apex predator? That’s kind of ironic. Had that encounter gone worse, a local headline might have read “local safety expert fails to heed own advice, gets killed by grizzly”. Fortunately everyone went home unscathed.

Darkly hilarious, of course, but is it hilarious for the wrong reasons? I have to laugh about it too, but I think the irony isn’t that profound. Safety is much more complicated than it used to be and how we relate to safety, at least in the West, has changed a lot over time. Few predicted its evolution better than Francis Fukuyama.

Retreat from Blood Ridge

While The End of History and the Last Man has faced plenty of criticism for its geopolitical theories, the second subject of the title – the “Last Man” – is solid. In one of the book’s most prescient chapters, Fukuyama states that “the last man at the end of history knows better than to risk his life for a cause”, having seen past generations’ grand struggles as pointless folly.

In other words, in the light of bloody, ideological battles, safety and health compose a new moral high ground. If we look around today, it is indeed difficult to critique someone’s choice to not risk their own life. When someone looks out for themselves they are typically not hurting other people or imposing upon the freedom of others. The choice to be safe is more than physical prudence – it’s also the safe option in social or political terms.

It might not be a coincidence that run clubs and biohacking scenes have taken off in concert with increasing loneliness and decreasing drinking. I think folks aspire to be virtuous, and if we praise rational behavior like avoiding silly risks, that feedback loop will generate more safety-obsessed people.

“When risk appeared on the stage, God had to renounce his role as lord of the universe.” - Ulrich Beck, World at Risk

Ulrich Beck, whose books I’m finally now getting into, has also documented how we’ve become increasingly preoccupied with safety. It’s a good thing we are, he says, because we have more and more risks to deal with.

As someone whose work is aimed at improving occupational health and safety – how could I discourage that? Aren’t we moving in the right direction?

Yes and no.

The Creative Destruction of Care

Much of the health and safety boom is pathological. It’s spun off a massive industrial-grifter complex that shills supplements, useless exercises, and diet fads. We continue to chase diminishing returns in safety, sacrificing a lot of freedom and dynamism along the way. What’s considered a “mid physique” in 2025 was a super fit person in the 2010s. The zeitgeist of homo securitas – Safety Man – has affected everything from household hobbies to massively profitable AI labs.

Those are the bad things. A lot of safety initiatives are performative at best, if not counterproductive or outright scams. They are the destructive side of this change. A kind of iatrogenesis (harm caused by medical intervention). But there are also some positive developments. Before I get into those, though, it’s worth looking at the different types of safety.

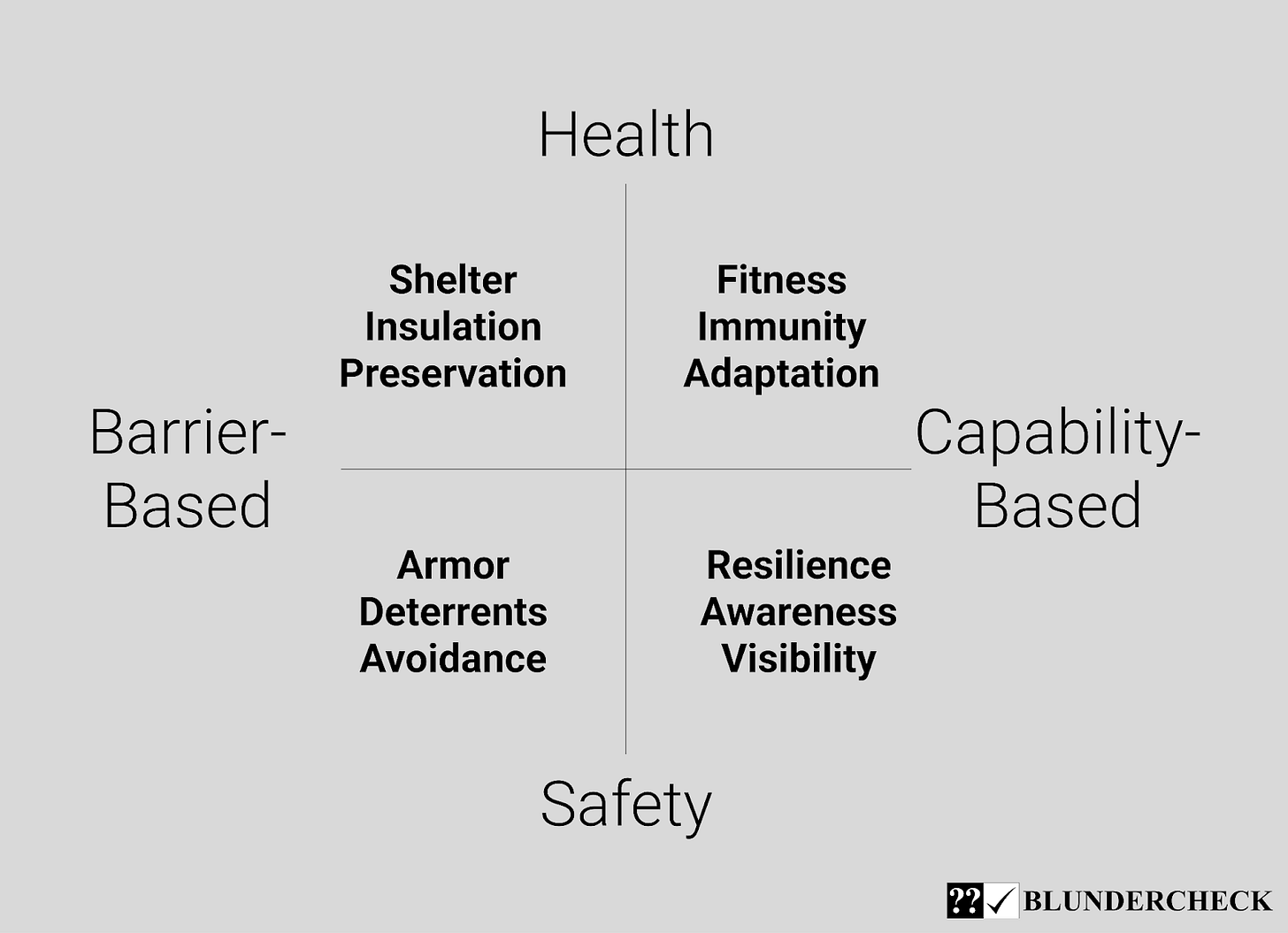

I’m a huge proponent of capability-based health and safety. Barrier-based approaches work just as well, but have more side effects. First of all, they’re more fragile and context-specific than capability-based approaches. For instance, metabolic health has plenty of benefits whereas a backbrace might produce one or two. They also tend to displace risk onto others. For example, purchasing a large SUV for your family is a reasonable safety measure – but then your family becomes a hazard.

This 2x2 has obvious limitations. A bike lane is a barrier-based safety intervention, but it’s one that doesn’t displace risk. Still, it’s useful, because it orients you towards the best types of approaches – capability-based, with zero or low risk displacement.

While our overall arc towards homo securitas has some cons, I think there are pros as well. Some positive developments include: social media, wearables, and consumer health services. I’ve changed my mind on a few of these, most recently psychological safety.

Social media

As much as TikTok might be a scourge on people’s mental health (that’s a problem I’ve written about) social media constitutes a huge improvement in planetary visibility. Visibility is a key factor in workplace safety. Dark spaces are notoriously more dangerous than well-lit ones. Same goes for hazards across the globe.

There have been several, mostly unsuccessful attempts to create international workers unions. We still don’t have one that meets the political slogan “Workers of the world, unite!” used by Marx and Engels. But social media is a surprisingly close second – it’s harder to control than traditional media, which makes it an effective way for workers to “illuminate” the global economy’s pinch points, like coal mining in Pakistan.

Cameras and internet connections aren’t a direct fix for these sorts of health and safety problems, but I believe they tend to reduce the time-to-solution. It’s a paradox: as we improve our ability to see hazards, the world will come to contain fewer of them.

Wearables

As they are now, I think wearables are kind of trash. The metrics they use aren’t that useful and tend to make people more anxious (that’s often a good thing) than anything else. Consumer wearables have a lot of untapped potential but for now remain a part of the industrial-wellbeing complex. Feedback loops that get people to move more are a great first step, but what else could wearables do?

They could help us detect epidemics faster, improve workplace health outcomes related to stress, give early warnings about cardiovascular trends, help folks get better sleep… plenty of opportunities. So why hasn’t it happened?

Obvious issues of behavioral change aside, we need target, intelligent standards for sensors. Health wearable data needs to be more interoperable to be useful – especially for public health use cases. We already have the cryptographic tools to encrypt and anonymize data, but we won’t unlock any large-scale benefits without better standards at the hardware level.

Marco Altini is doing some great work on wearables.

Psychological safety

When psychological safety burst onto the scene in the past decade I had some apprehensions. For one, it seemed gratuitous to refer to things like self esteem as safety issues when people lose limbs in sawmills and die in car accidents. The term is an obvious offshoot of the broader rise of noble safety and, because of that, I had doubts. But it continued to have traction and while I still have gripes with the semantics of it, the concept is useful – for three reasons.

First and foremost, the main risk factor for the top work-related causes of death today (stroke, heart disease, COPD) is long working hours. Long working hours are stressful and the adaptations we make to environmental stress (read: coping mechanisms) tend to be unhealthy. Psychological safety aims to reduce stress, while keeping upward pressure on productivity, which is a great thing for both workers and businesses.

Second, psychological safety is about managing expectations. Many employees sandbag – which is a term in chess for hiding your abilities or ranking to get into a weaker pool of players. It’s effectively cheating, but workers often do it because missing quotas or targets is super stressful. Psychological safety helps teams improve visibility into performance and capacity without trying to squeeze every drop out at all costs.

Third, it helps us treat mistakes and near-misses appropriately. Everyone makes mistakes. Over the course of your career you’ll continue to make bigger, and bigger, and bigger mistakes. That’s a natural consequence of more responsibility. The trick is to not make the same mistake twice. Near-misses are also valuable, and the concept of psychological safety frames near-misses as free lessons.

Psychological safety really should be called something else. If you have ideas, let me know.

Congrats on 500! 😄 (I'm just 2 away from that, so maybe we can crack open a beer shortly lol)

Regarding your research on safety, I'm enjoying what you put out into the world on this Substack, mostly because I love seeing thinking emerge through writing. I've consulted on a fair amount of workplace safety culture projects myself, mostly in energy and manufacturing, and I have to say your research into the protocols side of things – in contrast and in complement to my more narrative side – presents tantalising synergies…