How to Flip a Gestalt Switch

The simple, exhausting, and only way to change your mind

It’s easy to lose the forest for the trees. The right way to find it isn’t by becoming an arborist. Nor can you always rely on zooming out – we’re in the things that we observe, and we can only get so far outside of ourselves.

Sometimes you must flip a gestalt switch to see the bigger picture.

When you learn about someone’s philosophy, it’s not like you suddenly become convinced. There’s just too much to unpack and too many things about yourself that would have to change right away. It’s a lengthy process of immersion, where you have to become saturated with someone else’s thoughts and feelings. At some point in that process your gestalt switch flips.

In other words, our perspective is weighed down with inertia.

The phrase “let’s look at this through a different lens” should bring to mind an image of a gigantic magnifying glass too large to move without a crane. It takes a lot to change your focus. The only way to really get it is to immerse yourself.

One obvious example of immersion’s necessity is cultural dexterity – the ability to pop between different cultures. There are plenty of heuristics that chart cultures on aspects like power distance and openness, but those aren’t enough. I’ll share a bit more about my two years spent learning French in Québec in a moment, but I’m already overdue for an example of Gestaltism.

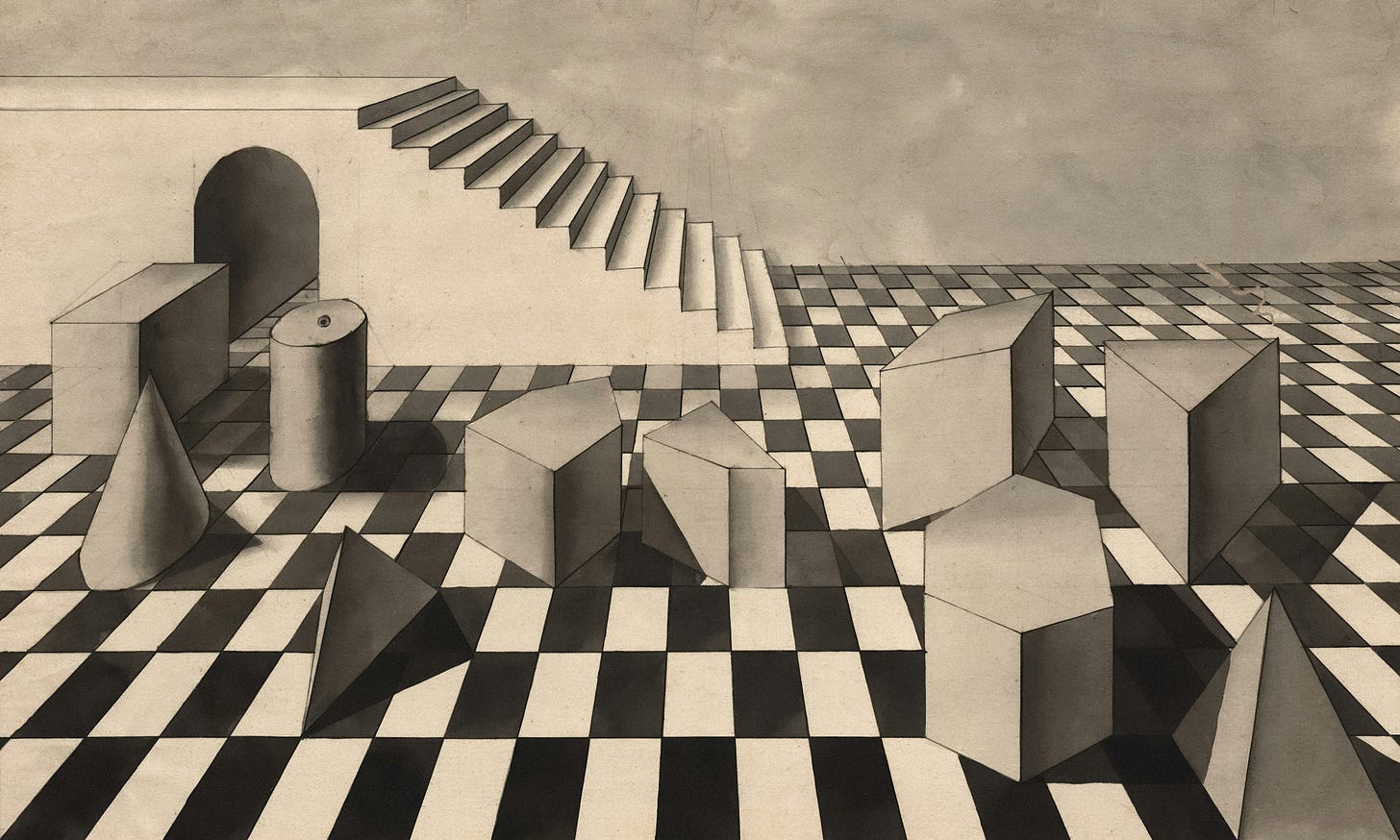

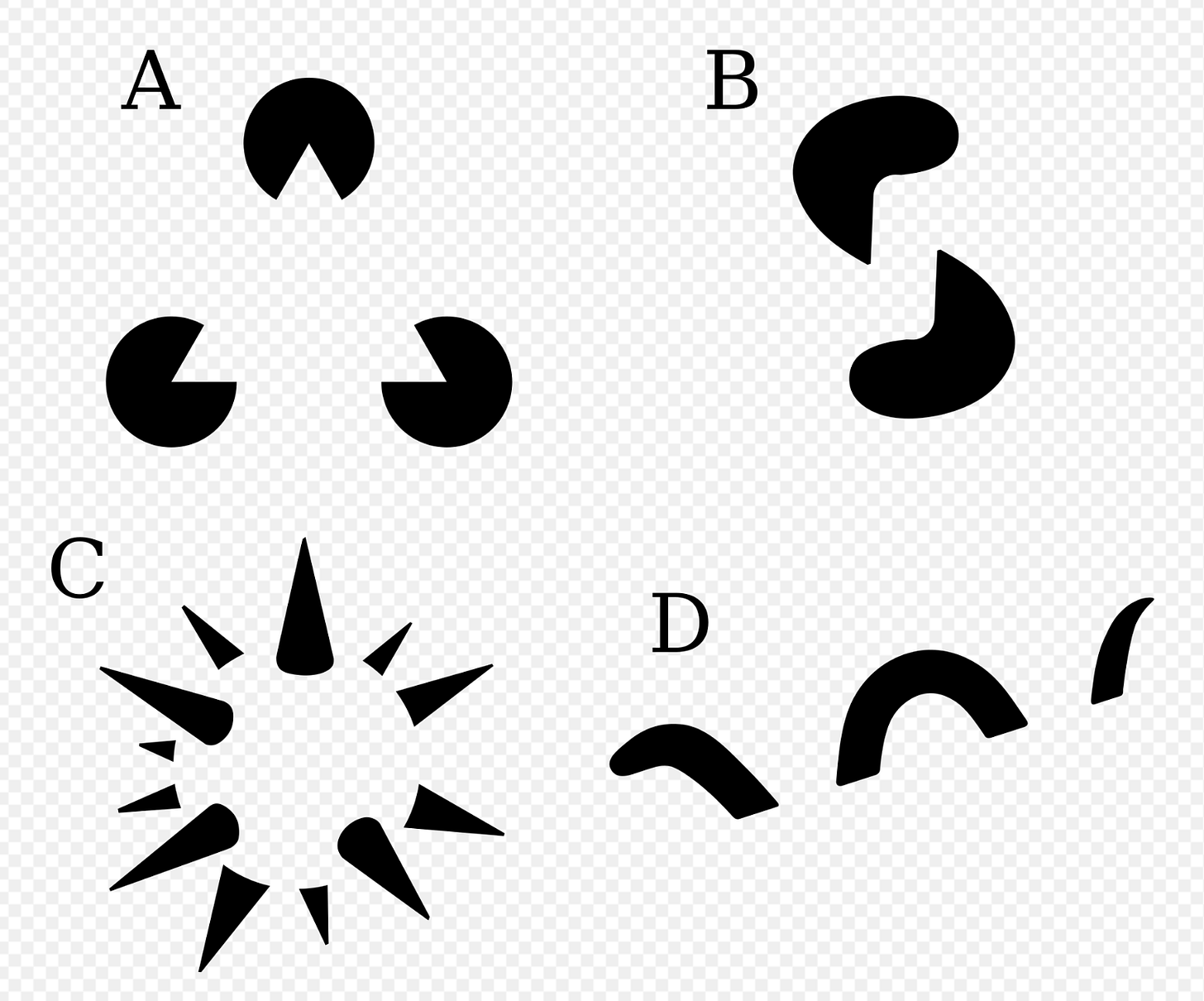

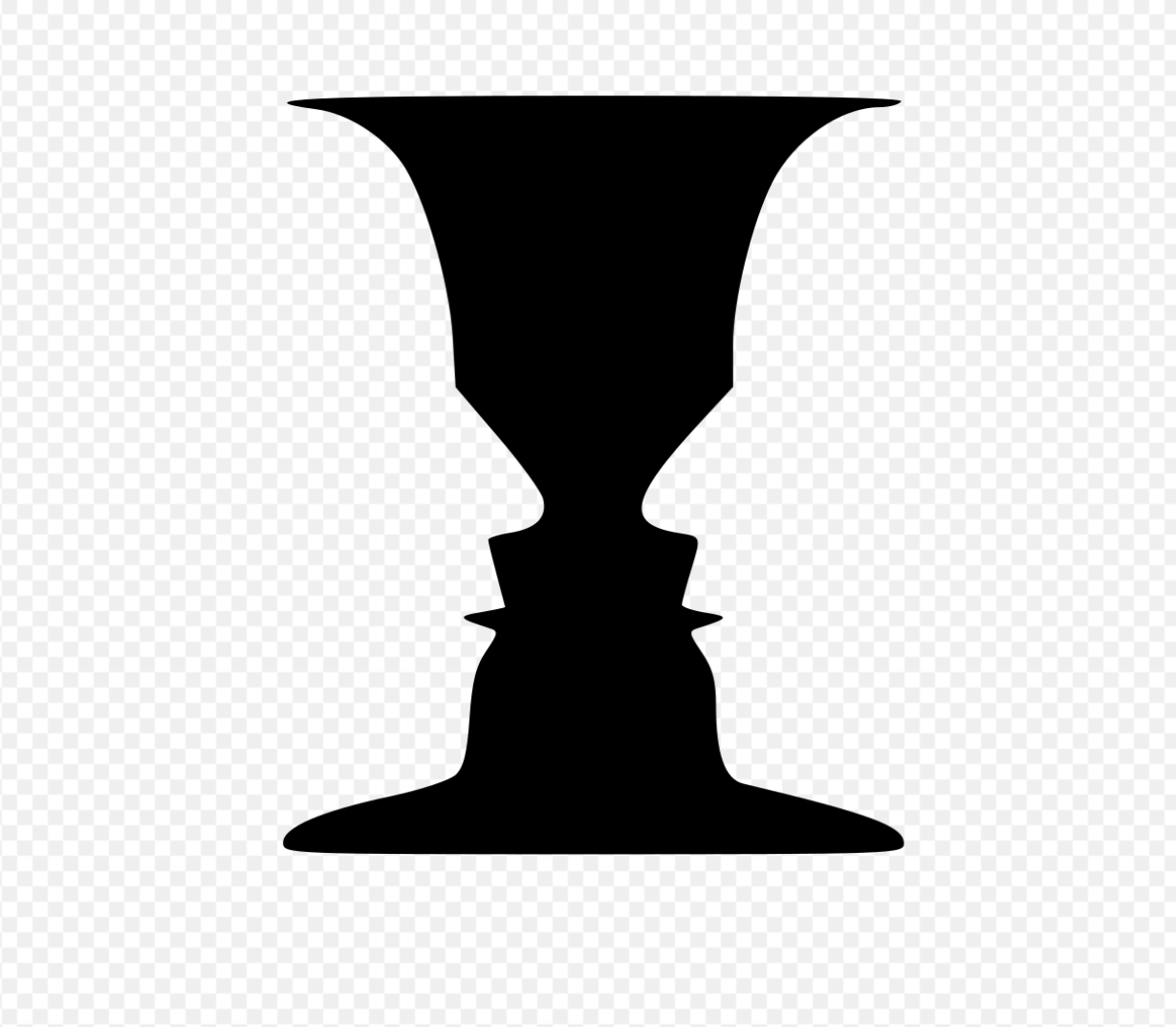

I bet you’ve seen a few images that illustrate the principles of gestalt psychology. They look like trippy optical illusions. And, since our eyes aren’t the only way we perceive the world, doesn’t it seem likely that there are many other gestalts (organized wholes different than the sum of their parts) that we miss for the trees?

It would be convenient if we could zoom out, but we can’t. The only way to pull your perception out of a mix of incoherent parts is to map them, like a lone, blind man touching an elephant. The acquisition of each data point is laborious, if not dangerous.

But there’s no alternative to immersion.

A fact will never change a mind as much as a friend can.

Raw, objective analysis is too flat, too slow, and too cold.

Anything worth doing is worth doing to excess.

It’s more fun.

Anyone who’s learned a language or binged an author’s work will understand how immersion triggers a gestalt switch. I’m still not silver-tongued in French, but the majority of my lessons were weekends spent with friends and family in Québec, not lectures in a classroom.

Classrooms treat you like a piece of mud. They pile you with layer upon layer of grammar, syntax, and vocabulary. The hope is that those layers of sediment will form a stable structure that you can carry with you, but most people who stop taking lessons simply erode.

The superior way to learn is through immersion – through an igneous process of learning, not a sedimentary one. Getting a rock to melt and snap its molecules into new formations requires a lot of heat.

Every time I immersed myself in a francophone environment, I could feel my brain melt and snap into new shapes… just to get me through the weekend. It’s far more effective to learn French from people who don’t really speak English. Being in those environments was a sure way to flip my gestalt switch – I might not have known the language, but I definitely felt like I got it.

We learn through association, not argumentation. It’s easy to bounce off another person’s ideas when they explain it logically. Indeed, we’ve already made up our mind. So have other people. You change your mind by hanging out with people who see things differently than you. You might not ever be persuaded to your core – but you’ll get it.

“We can know more than we can tell” – Michael Polanyi

Seeing many sides to one picture is a double-edged sword. The more times you trigger a gestalt switch, the more perspectives you expose yourself to. When the world is full of multistable objects you can become metastable – unable to commit to a side.

It might very well be a good thing to have that inertia in how we perceive the world. On average, our beliefs aren’t transformed or hijacked by simple phrases and sentences. That’s a good defense against enterprising advertisers.

That said, being able to flip a gestalt switch is valuable. Without that ability you would lead a myopic life. It’s a nauseating process sometimes, especially with things as difficult as learning a language or studying a new field. Like writers typically hate sitting down to write, but enjoy having written, flipping a gestalt switch through immersion is a similarly enjoyable process.

Protocols, like languages or philosophies, demand immersion. It’s not enough to just observe them. You can’t work around or ignore them. Working with protocols is an immersive experience, both in terms of adoption and design. They’re a clear example of non-visual gestalt switches.

Protocol adoption results in a non-naïve version of learned helplessness, in which outsourced actions or decisions enable focus on more important things. Design requires one to work through the protocol, to see the gestalt (the protocol’s argument), before you can re-engineer it.

“…it is through protocol that one must guide one’s efforts, not against it.” – Alexander Galloway

This idea of gestalt switches fits into a couple of recent ideas on my mind, namely mentabolism and analytical brainrot. It might also have relevance to marketing (in the Grabowskian sense) because, essentially, you must flip other people’s gestalt switches if you want them to buy something that’s fundamentally new. And you need to find clever, persistent ways to do that because people’s views are inertial.

There’s no shortcut to flipping a gestalt switch – only the long, difficult work of staying in the picture until it starts to look back at you.

This has given me a good idea on how to sell something I’m currently making. It will not be enough to show how it works (better) but to show how everything else works (worse). Thank you.

Immersion is the way to develop the aesthetics of a particular perspective, culture, or environment. Playing with the paradox of holding multiple perspectives (lensical or dragonfly thinking), with a learned ability to appropriately do the Gestalt context-switch, might be the best way to develop resilient, adaptive multi-stability.