Frankenstein's Holiday Guide to Personal Branding

Self-assembly > self-reflection

Happy holidays everyone. Last post of the year for Blundercheck – see you in January.

Typical writing wisdom dictates that confidence reads better. Don’t say “I think…” Just say what you think. Normally I follow that advice, but today’s post demands an exception. This is a little guide to personal branding, which I do an egregious job of. Read at your own risk!

Internet branding basics are well-covered: consistent profile picture, polished copy, updated social media pages, post regularly, stick to one topic, etc.

Instead, I want to focus on a (paradoxically) more human approach to personal branding. It’s probably wise to candy paint your brand afterwards, using the more traditional methods I mentioned, since this guide will turn you into a monster.

Frankenstein, the monster dreamed up by Mary Shelley, is a sapient assembled from different people’s body parts. Its monstrosity is partly rooted in being a zombie, but mostly in being a meat puzzle.

Few people would take inspiration from Frankenstein regarding how to construct their own image. In practice, it’s a common methodology, hence the phrase: “We are the best parts of the people we meet.” The only difference is that interesting personal brands are assembled from living people’s traits, rather than dead people’s limbs.

Two examples before I share some tips, tools and tricks. First is Timm Chiusano, whose reels about thriving in Corporate America and practicing appreciation are like catnip to me. Second is Ben Thompson, founder of Stratechery and analytical powerhouse, who many of you reading will be more familiar with. Chiusano and Thompson have slightly different approaches to Frankenbranding, but are clearly both good at it.

Case I: Splicing

Timm Chiusano is a content creator and writer best known for short, quietly charismatic videos about work, appreciation and navigating corporate life without losing one’s humanity. His online presence – primarily on Instagram and LinkedIn – sits somewhere between career advice and gentle social critique.

Rather than offering optimization hacks or hustle rhetoric, Chiusano focuses on tone, posture and mindset: how to show up well, how to notice what’s working, how to be generous with credit and how to build a life inside institutions without becoming flattened by them.

He also provides an excellent first case study for this guide because of his transparently Frankensteinian approach. Obviously, he’s got his own personality, vibe and style (gentle, high-achieving and hip) but in terms of his brand, you can see the stitches connecting its constituent parts.

Chiusano’s not shy about it. In a recent Instagram story, he shared a list of people whose parts he’ll build a brand from in 2026, such as famous vlogger Casey Neistat and American TV personality Mister Rogers. It was a really good list and I’m sure it’ll work, just as it has in the past. No surprise from me when his account crosses 500,000 followers in the next couple of months.

People have been doing the same thing with vision boards for a long time. There’s a liberating element to splicing personalities and styles together. It’s very unlikely that you’ll find a commercial, off-the-shelf brand that will fit you. And if imitation feels wrong, it’s temporary. Unless you totally lack curiosity, you’ll naturally branch out looking for new genetic material for your brand.

I’ll save my jeremiad against self-reflection for the next case study, but safe to say that our friend Frankenstein would approve of Timm’s splicing approach.

Case II: Patchworking

Ben Thompson is an independent technology analyst and writer best known as the founder of Stratechery, a subscription newsletter launched in 2013 that helped define the modern category of paid, single-author internet analysis. His work focuses on the strategic dynamics of technology companies – particularly how distribution, aggregation, incentives and business models shape outcomes over time. For many readers, Stratechery functions less like news commentary and more like an ongoing seminar in applied strategy.

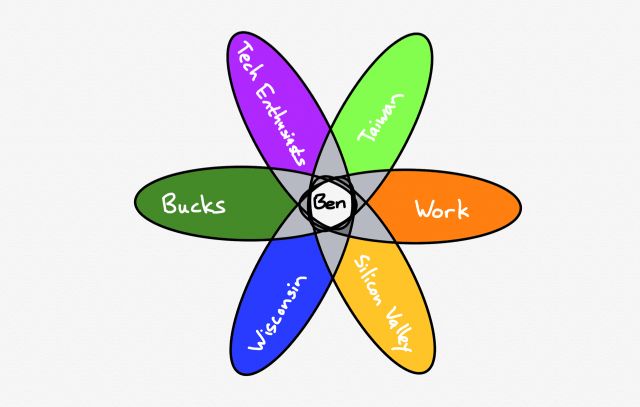

Thompson’s approach to branding could be called patchworking. First and foremost he’s a technology analyst. But he’s also a fan of the Milwaukee Bucks, a (now former) resident of Taiwan and a thorough Wisconsinite.

What’s less obvious about personal branding is the role it plays in, well, your personal life. Most people can’t sustainably base their entire lives on work. It’s important to have outlets, escapes, backup plans, external motivations, non-work friends and curiosities that aren’t directly profitable.

The default approach to this problem is to pick an existing bundle. You live in a city, climb the ladder at a local company HQ, cheer for the nearest football team in the state and pay attention to your national elections. Obviously, logistics can make this an impossibility.

While soul-searching via patchwork might feel alien, Thompson argues that it’s not just an alternative approach, but an objectively better one (bold mine):

“The pride arises from a piece of advice I received when I announced I was moving back to Taiwan seven years ago: a mentor was worried about how I would find the support and friendship everyone needs if I were living halfway around the world; he told me that while it wouldn’t be ideal, perhaps I could piece together friendships in different spaces as a way to make do. In fact, not only have I managed to do exactly that, I firmly believe the outcome is a superior one, and reason for optimism in a tech landscape sorely in need of it.”

It’s tragic that personal branding has become so deeply associated with knowing thyself and introspection. More important things in life require enough of both of those. Personal branding should be fun and less limiting.

Frankensteinian self-assembly > Freudian self-reflection.

How to Frankenbrand

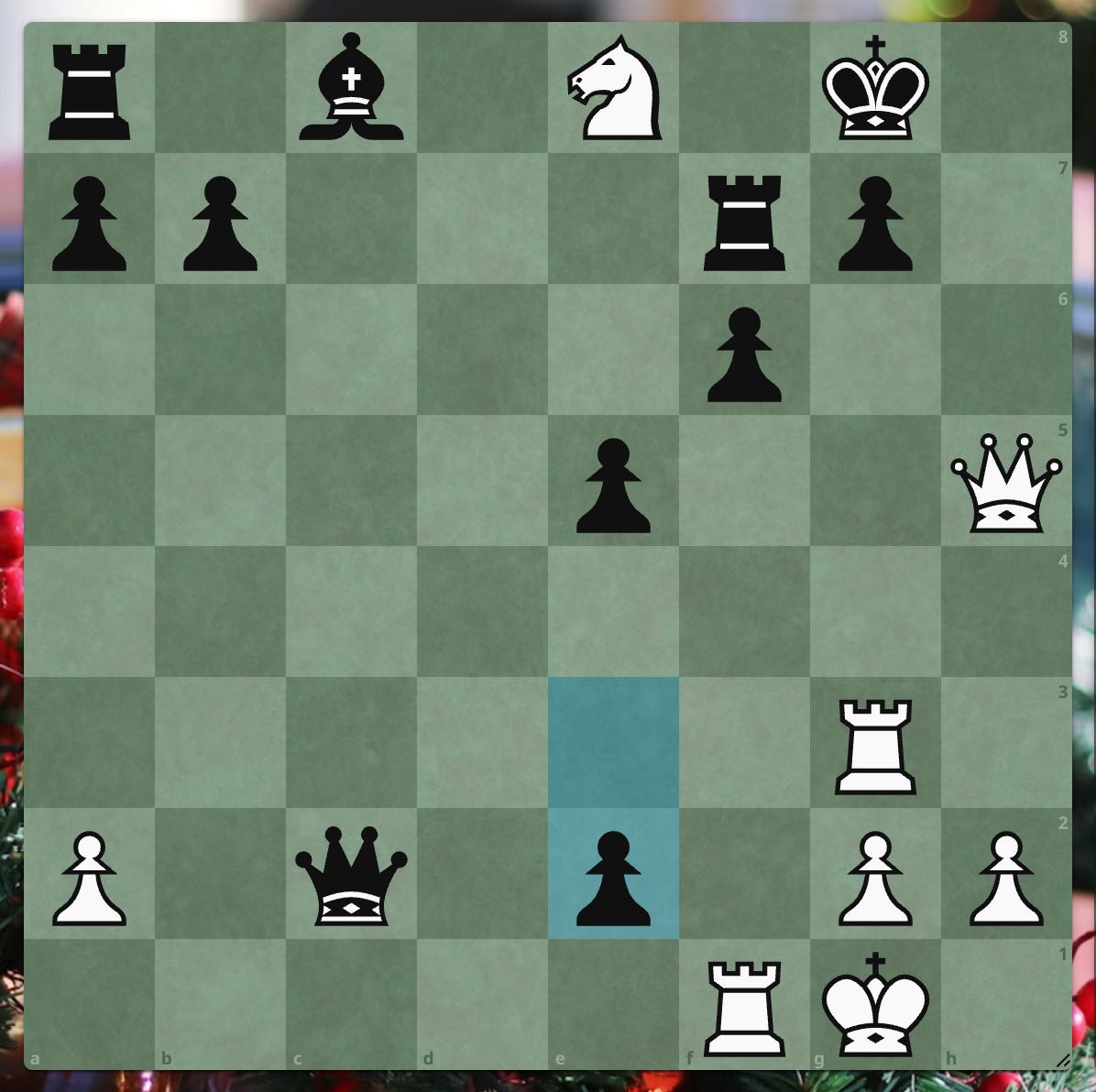

Again, this is not my forte. However it’s a current project and I’m slightly qualified to comment on it. Blundercheck is a frankenbrand – a mix of safety, tactics, chess, risk and work content. It was hard to find a word strong enough to stitch those ideas together, but incredibly satisfying when I did.

Here are some methods and heuristics that I’m using:

Gravedigging: unlimited use of parts of other people, such as those whose work I admire in some way, like Chiusano, Thompson and others like chess player Daniil Dubov. It’s useful to have a diverse mix of “cadavers”.

Backronyms: this is a naming technique, but the logic applies. Choose a desired word or end state, then backfill as needed to create the whole. For example, C-3P0 is the protocol droid in Star Wars and if I wanted to create an institute called C-3P0, I’d pick 5 suitable words starting with C, P, P, P, O… Center for Protocolization Policy and Progress Observation.

Venn diagrams: write down the names of different people or ideas you’re interested in. Draw a circle for each, overlapping them where you feel there might be some shared elements. Describe and name the overlaps. This should get exponentially harder with the number of overlapping circles.

Counterprogramming: define a couple of things you refuse. Otherwise, you’ll feel tempted to incorporate everything into your frankenbrand.

Multiple Objective Principle (MOP): every post, product, or piece of content should do at least two things or emulate at least two of constituent parts of your brand. Always accomplish two things at once. Always be mopping.

Electrification: it’s okay to leave the stitches showing, but the thing needs to come to life. Jamming 2+ ideas or vibes together is just a perverted act of taxidermy unless it forces a creative synthesis.

Frankenstein’s compass: if a personal branding project begins to feel like therapy, journaling, or self-reflection you’ve gone too far. It should feel more like collection and curation.

Many people are feeling pessimistic about how their relationship to the internet. However, you have access to inspiration, ideas, communities and fresh problems to solve like never before. Branding like Frankenstein is monstrously fun and the superior outcomes it generates are a reason for optimism in a media landscape sorely in need of it.