A Jury of Mirrors

Avoiding the Ingroup Opening Trap

If you’ve never heard of the long game, I’d recommend this set of aphorisms to get you oriented. They’re written by Yancey Strickler, cofounder of Kickstarter and Metalabel. In short, the long game is just as much about winning as it is about not losing. We all play long games. But who do we play them with?

We just recorded Bridge Atlas - Episode 3 with Yancey and Trent Van Epps. Trent is one of the brains behind Protocol Guild, a project that supports open-source software commons by funding its maintainers.

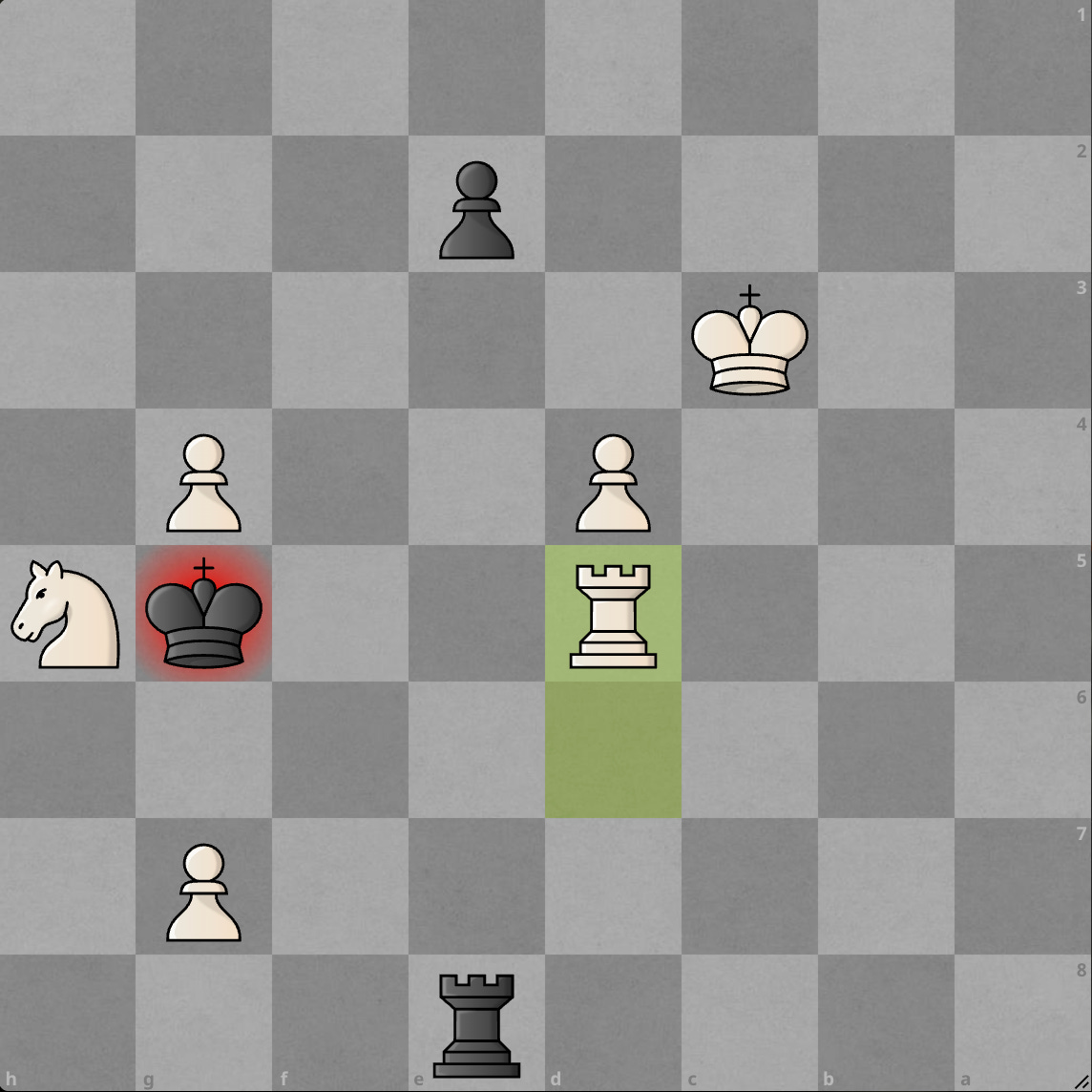

Blunderchecks are about enabling yourself to play the long game. Chess is really a terrible game if you lose in the opening. My first game, in high school, was like that. I thought my pal was an easy mark, then I waltzed into the cringeworthy scholar’s mate. The game was over in three moves and I didn’t play again for three years.

Now, I’m pretty good. In 2021, I won the UVic alumni chess tournament. It’s a nice hobby and part of me wishes that I learned earlier. A live, long game of chess where you get to take your opponent into a dark forest and see who comes out alive is a joy – but it requires not blundering.

The Ingroup Trap

The joy of the long game is what makes learning the dull parts worth it. I use the word dull because a cut from a dull knife hurts a lot more than a sharp one. Like having your ego stabbed with a cheap chess opening. Better to avoid such things altogether rather than make the mistake yourself.

Life is full of long games worth playing. Art. Building a brand. Physical training. Business. Family. Tuesday Night Music Bingo.

One common way to lose your path to the long game is a jury of mirrors. To aim at impressing your peers. To fall into the ingroup game. Why do you need to avoid this?

Because the long game is always played with the outgroup, not the ingroup. As one of my colleagues likes to say, “The future isn’t just today plus your thing. It’s today, plus your thing, plus everyone else’s thing.”

Unless your group is in charge of the future, you’re playing a game with many other groups. The math is simple: your ingroup is a fraction of the total system, so the long game—by definition—is decided elsewhere. If your moves don’t land beyond your peers, you’re not actually playing the long game, you’re just winning practice rounds.

Insulating yourself from others is an easy way to lose the game.

Avoiding the Edges

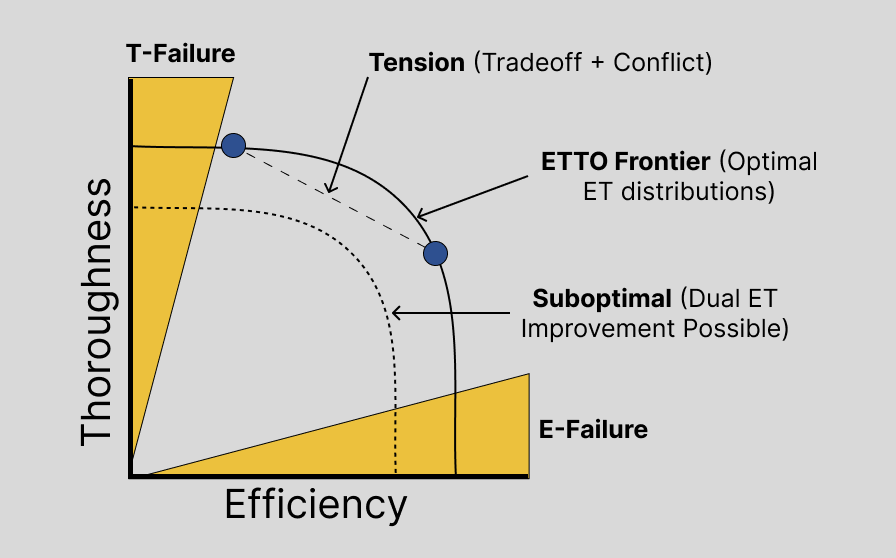

Efficiency-thoroughness-openness trade-offs (ETOTs) are the reason that groups are eliminated from the long game. Survival is out of the question if you become too extreme. It’s easy to become extreme if you’re in an arms race. Just like in chess, you want to carve out a position in the center of the board.

“A knight on the rim is dim.”

Take, for example, three different groups: bodybuilders, runners, and academics. It’s very easy to assemble a jury of mirrors by accident. The judges for Mr. Olympia are all former bodybuilders, and those competitions have become extremely niche with nearly no popular appeal. Runners push each other to the point of developing arrhythmia, thanks to Strava-like dynamics, and academics get into citation circle-jerks.

It’s a product and marketing concern too. A lot of products are developed by engineers who are bored and trying to do something impressive for their peers. Then they take a Plumbus to market and nobody wants it, even after everyone inside the firm was confident in it.

Bodybuilders should try to impress runners, academics, and engineers. Engineers should try to impress non-engineers. One of the fundamental implication of the ETOT concept is that you need to avoid the edges (see below). That’s not enough to guarantee a win, but that’s not the point. The point is retaining your option to play the long game.

You really want to avoid falling into the ingroup trap. It feels paradoxical in practice, at least partly due to the common adage, “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” This is excellent advice for anyone planning an outdoor excursion, but requires some nuance before being ported over to other long games.

Niches vs. Arenas

The long game is about finding a niche. Narrow ingroups don’t have niches. They have arenas, which are fun and can help you grow, but you can’t live in an arena—at least not for long—because there’s not enough safety or interdependence. If you spend all of your time in arenas, you’ll eventually lose your spot near the top. Humans are fortunate to be only partial tournament species. We can have a foot in both the world of arenas and niches.

When you fall into an ingroup trap you lose the ability to secure a niche. Let’s go back to the examples of lifters and runners. These loosely correspond to two broad cultural movements, both of which have formed a jury of mirrors. Lifters compete on muscle mass and machismo. Runners on 5k times and VO2 max.

You can kind of see how these might map to political ideals at a macro scale. The lifter’s bulk-cut cycle corresponds to ideas about intentionally crashing the economy. Degrowth rhymes with endurance training methodologies that emphasize building a solid base before ramping up.

Both at a micro- and macro-scale, lifters and runners have fallen into the ingroup game. Elite runners have arms that look like spaghettini. Elite lifters look like the Michelin Man. “Runner States” and “Lifter States” both fail in their policies, because their policies are written by wonks, for wonks.

This sort of feedback loop becomes bad when it turns chronic. Avoiding it isn’t enough to win, but it’s enough to not lose. And in long games, not losing is almost equivalent to winning. We’ve seen enough people fall into this trap (like poor Grade 10s falling into the Scholar’s Mate) to now avoid replicating it ourselves.

A Checklist

There are many ways to avoid constructing a jury of mirrors. Avoidance strategies are also context dependent, but there’s some underlying logic from which we can make a checklist. I’d follow it if I were you. The jury of mirrors is a common failure mode in all kinds of long games. You have to avoid it.

Turning winners into judges. Pushes things too far via aggressive one-upmanship.

Trying to impress your competitors. Your competitors aren’t your audience, the judge, or your friends. Who cares.

Confusing dominance for mastery. Conquering an arena doesn’t translate to other skills automatically. Great players don’t always make great coaches.

Mistaking speed for progress. Confirmation from peers accelerates, input from the outgroup often slows things down – but can harden things.

Over-specializing in your admiration. Don’t become someone else’s mirror. Only admiring work like yours is a dead end.

You need to stay alive long enough to find the forest, where all the fun happens. Thanks Yancey Strickler and Venkatesh Rao for shaping my thinking on this one.

One particular interesting question buried in all of this is *how to build yourself a niche*? This reminded me of „Skill stacking“: the idea that instead of trying to be the very best (read: extreme) in one very narrow field, you should/could strive to carve out a niche by being quite good (read: not extreme) at a sufficiently diverse set of skills in different domains which combine into a unique pattern of skills that are useful when put together. Not necessarily as a deliberately planned attempt but more as a natural outcome of interest, talent, and acquired skill.

Takes some time, but keeps you checked from blunder.

Tomas Pueyo had a nice article a few years back on that:

Pueyo, Tomas. “How to Become the Best in the World at Something.” Substack Newsletter. Uncharted Territories (blog), September 2, 2021. https://unchartedterritories.tomaspueyo.com/p/how-to-become-the-best-in-the-world.